MOTHER TONGUE by Adil Tuniyaz trans. Munawwar Abdulla

We were born like gold

on this sparkling brown land.

It fell, ringing

from the mouth of an Uyghur angel,

its music sunk into our ears.

Oh, mother tongue,

we became wanderers,

and have moved far from your horizons.

Opium poppies

bring the scent of the seas,

thoughts kept moist for a while.

I have left the radio on.

It speaks

in the wind.

Cool orchards

Oil, sandy mountains

A group of people whose colours have drained,

dead still cities and winter pastures.

I drank coffee

and cried.

The ocean waves entered my home.

A note on Adil Tuniyaz by Munawwar Abdulla

The current whereabouts of Adil Tuniyaz is unknown. Most likely, he is in a jail in Urumchi, the capital of occupied East Turkistan, in Xinjiang, China.

Adil Tuniyaz, his wife Nezire Muhammad, eldest son Imran, and father-in-law Muhammad Salih Hajim, were all arrested in December 2017 during the Chinese government’s mass incarceration campaign that displaced millions of Uyghurs into re-education camps, prisons, and forced labor factories. The official charges for Tuniyaz and his family’s arrests were “promoting terrorism and religious extremism”. Multiple sources have speculated that the family were detained for their work translating religious texts such as Islamic hadiths into Uyghur. Muhammad Salih Hajim was a prominent religious scholar who was credited with being the first to translate the Quran (with permission from the government). He was confirmed to have died in a re-education camp in January 2018. It is difficult to know the current status of the rest of the incarcerated family.

China has denied the existence of “re-education” camps, then rebranded them as vocational training centers, then defended them as deradicalization training, and now claims that they have closed. Still, the number of prison sentences have skyrocketed, and many of those camps have always been attached to forced labor factories. People from every age group, religion, career, or academic background were targeted with no opportunity to ask for evidence for arrest or appeal for release.

Along with the crackdown on bodies, there has been a crackdown on thought. Knowledge. Language. Many writers, artists, publishers, even literature and anthropology professors, have been given long prison sentences for vague reasons with no trial. Tuniyaz’s cohort of modernist poets included Perhat Tursun, a controversial and secular writer who is now serving 16 years in prison after being arrested in January 2018 for unknown reasons. Another is Tahir Hamut, who managed to escape to the US and write about his harrowing experiences as an artist navigating state control in his book Waiting to Be Arrested at Night (2023).

While we wait to hear of Adil Tuniyaz’s fate, it feels important to share his old poetry. We sink into the softness of his longing for familiar sounds and horizons while in a foreign land. We think of his connection to identity and the way he transposes Islamic mystic elements onto Uyghur cultural motifs. I marvel at the scents and melodies he infuses into his poems. And I note the irony of translating a poem called Mother Tongue, and wonder if I have become unanchored like him, and maybe I should drink coffee, and maybe I should cry.

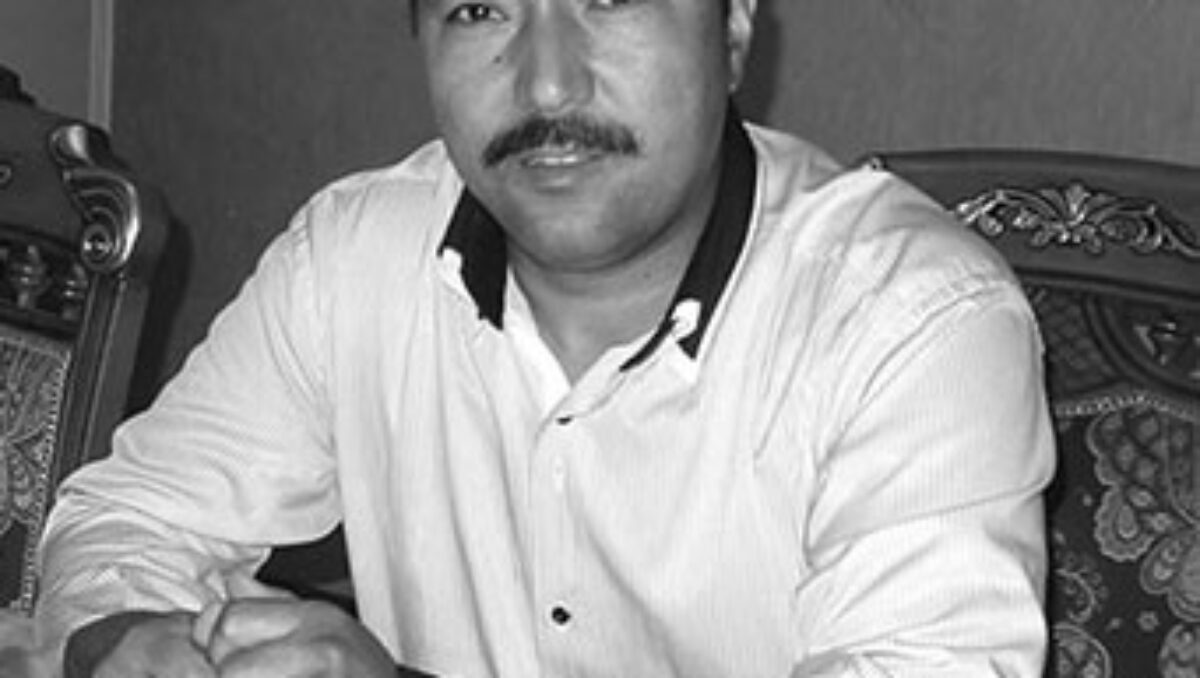

Adil Tuniyaz (b. 1970) is a well-known poet, journalist, and author of the books Questions for an Apple and Manifesto for Universal Poetry. He is often considered to be among the first generation of modernist Uyghur poets. Publishing his first poem in the journal Xinjiang Youth Daily at just 12 years old, Tuniyaz continued to pursue his passion for literature at Xinjiang University in Urumchi. After graduating in 1993, he became a journalist for Xinjiang Radio while continuing to publish his poems in literary journals, as well as several of his own collections of essays and poetry. In the late 1990s, he left his journalist role to continue his literary studies in Saudi Arabia, returning to Urumchi a decade later. In 2015, he and his wife, Nezire, opened the Light and Pen bookstore. Tuniyaz’s poetry often touches on topics such as Islamic mysticism, Uyghur culture and identity, and many contemporary themes that have made him a popular poet in Uyghur society.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

I WILL REMEMBER by Rahile Kamal trans. Munawwar Abdulla

Today I did not comb my hair

I didn’t even look in the mirror

My kitchen greeted me icily

The walls eyed each other, but didn’t look at me

I wasn’t worth it to those four walls

It’s hilarious that my cat was scared of me

Is my appearance uglier than a cat

Is it so important to dress up

How did I get to this thought

To carry on for a day like I am not living

Doing whatever that comes to mind

To think like those who have gone mad

Firstly, I boiled the coffee in a saucepan

then added a touch of vinegar

I washed my socks in the dishwasher

Found holes in four places

tossed and turned it

and sensed that it was still sound

I tried calling my daughter mum

Can you believe she replied, yes my daughter

I will remember that my mother is also my daughter

I hesitated when it was my husband’s turn

because sometimes I do not recognise him

He has this one look

where my insides end up on my outside

That is the way I am tested

I will try calling him by another name

Wallander, I called, staring at him

Wallander is a Swedish inspector

He didn’t respond, so I repeated, Wallander

Your case is fairly complicated, huh

If we bear it for a day it will unravel itself

A gourd with no water will wear holes in itself from dryness

So he said, looking at himself

Carefully combing my unkept hair

I will remember my husband really is Wallander

The litterfall is my red carpet

The trees sway and flirt

On one foot I wear a boot, on the other a slipper

I wailed loudly in my Uyghur tongue

The Ili roads are winding, winding

On those winding roads, a pair of skylarks sing plaintive

Mournful skylark

I will remember the magnanimity of the trees and litterfall

I came upon a gaunt woman

She froze upon seeing me

then backed away slowly

barely holding back a laugh

Between the two of us one of us is crazy

I know I am faking crazy

If she is also faking crazy

it’s clear then we are both crazy

After the gaunt woman

I arrived upon a four-way intersection

Green, yellow, and red lights

were brushing the road’s pressure points

Ah the highest degree of mania

It is not at all like the imagination

The lights stand around

shining their eyes

There is only colour here

The colour yellow is calm

How mystical is the red

How loving is the green

Some people would say I was calm

when they became toothless snakes and bit me

They would say I was a loving woman

when they hid the sun behind their hems

They would say I was a mystical woman

when I became crazy like this

Again a green light

On yellow we prepare

Red summons

I raised my right leg

I raised it and

I saw a woman stretched out on the ground

Her white hair uncombed

On her right foot a boot, on her left a slipper

Mournful and restless

Oh, this crazy, whining woman

said the gaunt woman

whispering

Oh, this lunatic woman

said the cat

muttering

The woman lying on the floor looked like me

but was not me

The green light was still on

I will remember the countenance of the colour green

I recalled all my memories

My vinegar flavoured coffee

My holey socks

My daughter mother

Wallander

My litterfall

My madness

These are all my green lights

Rahile Kamal is a poet born in Ghulja, East Turkistan, where she worked as an editor, reporter, and editor-in-chief at the Ili Evening Newspaper from 1993 until 2004. She was a prolific writer, publishing numerous poems and other literary works in various newspapers and magazines, many of which received prestigious awards. However, after migrating to Sweden in 2004, it was only after 2016 that Rahile rekindled her passion for writing and began publishing again in journals such as Izdinish and Ittipaq. Her poems have been translated to Turkish, Japanese, Chinese, and English. In May 2022, she published her poetry collection titled Kamal is Gone in Istanbul, and she has upcoming work in the anthology Uyghur Poems, which will be published by Penguin Random House in November 2023.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation