Take Four: An Interview with Megan Staffel

In this installment of “Take Four,” we talk to contributor Megan Staffel about her short story “Saturdays at the Philharmonic” and her latest collection from Four Way Books.

FWR: “Like “Saturdays at the Philharmonic,” many of the stories in your book Lessons in Another Language portray characters in the midst of some form of sexual awakening. Though the stories are set in the late sixties and early seventies, the characters’ experiences with sex seem more painfully emotional than the narratives of freedom and personal autonomy we so often associate with that period. What are your thoughts on the relationship between subject and chronological setting?”

MS: Culture changes so slowly we don’t see the changes until we hold a memory against the present. In my last collection, Lessons in Another Language, I was compelled to revisit the period I grew up in through fiction because I understand it differently now that I am an adult. I feel a bit wiser because of experience, but I’ve also gained a different perspective through the cultural changes I’ve lived through. That’s where sex comes in. As a culture, it seems to me we are less naïve. I believe (I hope) we are more nurturing of young women. These are generalizations of course, and they’re suspect because they are generalizations, but that’s why we need fiction. Fiction gives us the specifics.

There was a house in my childhood that contained all of the things I didn’t understand. I’ve revisited that house in dreams and in stories. It’s a house my mother spent her summers in as a child and I visited as a child, a big and forbidding stone house built by my grandfather at the foot of a wooded hill in Connecticut. It had a distinctive sound, a wooden screen door snapping closed, and the distinctive smell of old fires in a stone fireplace, and these sensory memories are what launched me into the group of stories that make up Lessons in Another Language, most of which are about characters in the in-between territory after childhood, but before becoming independent adults.

There was a secret in every drawer of every cupboard in that house and in the early sixties, as I wandered about by myself, pretending I was Nancy Drew searching for clues, I found only the mangle sitting by itself in the center of a small room in the attic and in my grandfather’s dresser drawer, a collection of pornographic photos. At nine years old they were both frightening and compelling, but thinking about them now, they gain meaning. My perspective now, influenced as it is by the culture of the 21st century, prompts me to ask, why was it necessary to sleep in ironed sheets, and what an extravagant waste of time it was for the woman of the house to create them, and behind that question is a more interesting one: did my grandfather ever tell his wife his fantasies? I think not. I think they were both constrained by their ideas of married life. He spent his days on the golf course while she was in the attic, running wrinkled sheets through the hot rollers on the mangle, making them crisp and smooth.

When a story takes place is as important as where it takes place, and I would say that the word “setting” includes both place and time and gives them equal importance. The story you mention, “Saturdays at the Philharmonic” was written after the publication of Lessons, but it was written from the same retrospective point of view that inspired the stories in that collection. And yes, you’re right, the sixties and early seventies urged us to enjoy sexual freedom, but that was a reaction against the constrictions of the fifties and also, probably, a direct result of the development of a birth control pill for women. Yet as freeing as the pill was, it also wreaked emotional havoc because we were girls formed by the sheltering mores of the fifties. That’s what’s so fascinating about history. The extremes of one decade “correct” the extremes of the previous decade. For instance, that ubiquitous Beautiful Hair Breck blonde whose pale features were on the back cover of every Life and Look magazine I saw, was the utterly convincing messenger for Breck shampoo and the icon I and many other young girls worshipped. Her every hair was in place and her face was so calm it was death-like. That purity was the ideal of beauty we sought. That is, until the sixties bottomed out and Jimi Hendrix screamed, “Are you experienced?” Then, she was no help to us at all.

Where a story sits in time gives the writer a perspective to work from. It provides the particular images, sounds, and smells that bombard our characters, but perhaps most importantly, it gives us the context that pressures the choices a character makes in his or her life. When is often the subject of the story, but at the very least, it’s a supporting element, one that’s impossible to peel away from character or events.

FWR: I’m intrigued by the idea that, in a world in which generalizations are a necessary evil, fiction has the potential to provide us with specifics. It seems art is so often accused of being too generalized, too abstract to serve much of a purpose.

MS: I suspect those accusations are from people who aren’t readers, who haven’t had the experience of “living” in a story or a novel and then missing it when it’s finished. When you have truly inhabited a piece of fiction, long or short, it feels like a complete world and the odd and marvelous experience of reading fiction is that it’s both real and imaginary, actual and invented. That is, we are experiencing what are only black marks on a white background while at the same time, we are translating their message. The black marks don’t, of themselves, create the illusion of reality; they need to be partnered with a mind to create that illusion. They are the code we translate to get access. With movies and TV, there’s no code. But we must partner with text and that’s why it has the potential to envelop us. And when it envelops us in a complete way, that is, when the illusion it creates captures us so utterly we don’t question anything (i.e. we suspend disbelief) it can rescue us from the banalities of our culture.

Those of us who are readers depend on this form of rescue. The specifics in the world of a novel or story are the antidote for the mind-numbing generalities in the commercial muck we slosh through in our daily lives. We tune a lot of it out of course; we have to. I tune out most of it because I live in a rural place and don’t have a TV or subscribe to the contemporary versions of the Life and Look magazines of my childhood.

But still, I am part of it. Leafing through the New York Times “Sunday Styles” magazine I see the word Aruba, and then below it: “Unwind on one of the best beaches in the world.” The photo shows an empty beach with a hand-holding couple walking away from a rocky cove in loose, wind-rippled clothing towards the foamy surf. I am spying on them from a hidden vantage point somewhere above.

What’s being suggested? Sex, of course. The photo shows us a post-coital moment. And then there’s the word unwind, a gloriously general term with nothing but positive implications supported by the curving shoreline, the curving path of the footprints, the body-hugging style of the sheath dress the woman wears, the flapping, unbuttoned shirt on the man. It’s rich in implication but starved of substance.

Fiction writers manipulate just as boldly. Our manipulations, of course, have a different purpose: we don’t try to numb our readers, we want to wake them up, to remind them of the finite quality of our individual material existence.

I like the word “material.” I am an epicure of the material world, in love with the concrete, sensory plain that supports our existence on this earth and perhaps my underlying purpose, as a writer, is to steer my readers away from that Breck woman, that Aruba fantasy, those abstract and generalized visions, back to the disquiet of the sensory.

As I am writing this, I am sitting on the porch of this house I share with my husband. It is late August and I look out at beds of flowers. This summer I have planted a lot of long-stemmed zinnias. They are a great flower for cutting and a wonderfully generous creature because the more you cut its stalks, the more flowers it will produce! And so our house is filled with vases of flowers and each time I walk by them I admire the shapes, colors, textures. But they last only four or five days. The daisy-like heads on the zinnias fall over, and all their intense, startling beauty turns to dross.

In the sensory world nothing lasts. A flower in full bloom; a moment of true communication in a relationship; the infectious laughter at a dinner party; a phrase in a tune that is perfectly melded into a movement with a partner on a dance floor: these stunning moments all pass. And yet these are the concrete experiences that energize us. So we go to art because the painting, the photograph, the conversation in a novel are the only ways of keeping them with us.

And, in a wonderful way, the art that catches that perfect instant in time isn’t static either. That is, it doesn’t stay on the canvas or on the page; it visits and informs the actual. So, a particularly beautiful arrangement of flowers that sits in a window in my kitchen reminds me of Matisse’s 1905 painting , “Open Window,” where color literally leaves the petals of the flowers and rises into the air.

In Shirley Hazzard’s 1980 novel, The Transit of Venus, there is an amazing scene between the duplicitous Paul Ivory and his one-time lover, Caro Bell, when Paul Ivory confesses not only his affairs with men, but a dark moment from his early life that resulted in a death that was deemed accidental but in fact was not. “I killed him,” he tells her. “I thought you probably knew.”

Paul believes Caro knew because his rival for Caro’s love, Ted Tice, had witnessed the “accident” and guessed the role Paul played in it, and Paul assumed he had told Caro. But in fact, he hadn’t. This is a startling revelation for both the reader and Paul Ivory because it means that Ted Tice is a scrupulously moral man. Even though Paul Ivory had been his competitor, Tice did not malign him. He wanted Caro to choose which man to love on her own and not because she had learned that Ivory had a dark past. So when Ivory confesses all, Caro sees Tice differently, and for the first time in the many years he has pursued her, she is ready to respond to his romantic overtures.

It takes an entire novel to set up this reversal and though it’s a development specific to this group of people, it spills out beyond it. That is, because it’s so specific, its truth is universal. It illuminates the complicated layers of human relationships in general. What it suggests to me is that the tangles in my own life, though different, are not so strange. So this is another way fiction can rescue us.

And then there is the curious comfort of the invented world. I think it unites us with our more playful, childhood selves. I am a great believer in the adult necessity to “play pretend,” and fiction ushers us through that portal; it allows us to exit the real and experience the rejuvenating qualities of imaginative possibility.

I believe art helps us to accept life’s messes. It provides release through catharsis. But it can do so only if it relates to our sensory existence, that is, if it communicates with the same specific and material world we inhabit.

FWR: So, in a way, art not only gives us rich experience, but the possibility of revisiting and reinterpreting that experience many times. You say the stories in Lessons in Another Language were partly an attempt to revisit the cultural moment of your youth. The book, of course, presents specifics – material, I suppose – perhaps not all of which was originally present in your memory. What do you think it is about the act of writing itself that lets us access or interpret our experiences better than memory alone?

MS: In my brain, and I will assume that this is true for others as well, the stories I tell myself about events that have happened in my life have a minimalized quality, an owner’s shorthand, that makes them knowable in an instant and habitual way. When these stories are translated into a narrative that will make sense to someone who is not the owner, there is a great deal of invention. Memory is patchy and so the supporting material must be filled in.

Should it be filled in with the purpose of telling the truth or with the purpose of telling a particular story? As a writer, I never take the first option. I’m not a memoirist; I’m not interested in what we call objective “truth,” what actually happened; I’m interested in what almost happened or what might have happened. I am bored if I have to stick to what I already know. I want to throw the doors open and invent! Invention allows more light, more air and thus, a new perspective. Invention creates the possibility of discovery. Also, it eradicates the memory groove and that’s a good thing.

The story in Lessons In Another Language that is the closest to actuality is called “Daily Life of the Pioneers” and two marvelous things have happened since that story has been published. One is that I have lost much of the original memory because the invented narrative has taken its place. And the other is that the first time I read that story, my audience laughed. I was, of course, hoping that they would laugh, but they did truly laugh and they laughed not just once but frequently. So the “real event,” the summer that my sister and I were sent to an Alexander Technique and raw-foods sleep-away camp in the wilds of Pennsylvania, was changed forever. Now it’s funny and awful, so I’ve been able to abandon the original dark and serious version, the memory I used to have to drag around.

But the true value of invention is that it allows the writer to approximate the cacophony of feeling we human beings possess. It seems to me we are always at the mercy of inchoate feelings — they are massively conflicting and difficult to articulate. And then to make everything more challenging, the actual events of our lives often lack the spectacle that our feelings suggest. So how do you get at them? I invent. Invention is the tool that gets us closest to the expression of those feelings.

Here’s what I mean: When I was a little girl I joined a Brownie troop. It was probably about 1959 and my mother, an abstract expressionist painter who worshipped color and led a bohemian artist lifestyle, was minimally supportive of the whole project. When she could no longer procrastinate the purchase of the outfit, she took me to the department store and I picked out the brown dress, the brown belt and the brown socks. To be a Brownie, that was what you had to wear. We gathered these items and then, on our way to the cashier, we passed a table of Brownie extras, things to improve the Brownie lifestyle. One of those was a little brown plastic change purse designed to hang on the belt. Brownies had to pay dues at each meeting and the purse would give me a place to keep my money. It cost only ten cents and I wanted it, badly, but my mother was determined not to spend another penny on such abhorrent items. Quickly, she slipped it into her handbag. It was a small thievery and yet, relative to my decision to join the troop and aspire to be a good Brownie, it was enormous. I felt ashamed, scared, guilty, and desperately unhappy. My mother paid for the other items and we walked out of the store.

Were I to fictionalize this, I would have to add things to increase tension. Maybe there would be a store cop. Or maybe a cashier would look our way. Maybe the little girl character would notice mirrors hanging down from the ceiling to apprehend shoplifters.

Because that’s what it felt like my mother was. The filching of the change purse was huge and it was irrevocable. It put us on a path I didn’t even know existed. Yet for my mother it was a simple and very small incident; she was only out of patience, with me, with the culture, and with her life as it was at that moment in time.

Lately I’ve been working on a novella about a young woman’s first romance. As many of us do, she chooses an inappropriate boyfriend, a sex addict and compulsive liar, and gets so entrapped by his version of reality she forgets that it isn’t her own. It wasn’t until I had finished the story that I realized I’d made use of my first boyfriend. I’d changed his context and given him better accomplishments — the invented boyfriend was a professional dancer —whereas the only creativity the original possessed was a remarkable timing and visual acuity that allowed him to do a reckless highway ballet that should have caused accidents, but only caused a woman to drive up alongside us and tell him she was glad she wasn’t my mother because if he kept on doing what he was doing, I was going to be dead. Oddly enough, her words had no effect. He was high and I was so numbed by constant fear I shrugged it off.

When I recognized that relationship in the novella I was surprised. I hadn’t set out to use that material, but I think memory is always guiding us. From the perspective of my invented characters, that crazy summer of my life suddenly looked very different. For the first time, I could see the absurdity.

I hadn’t set out to use that material, but memory must have been guiding me. And now with the novella complete (I won’t say finished because nothing is finished until it’s published) I am pleased that I’ve fictionalized a secret time in my life. When it goes out into the world, and if it creates a spark of recognition for some readers, that’s the real pleasure.

|

Not since Alice Munro’s The Beggar Maid has there been a book which so articulately reveals the complex |

Megan Staffel reads “Saturdays at the Philharmonic”

|

More Interviews |

SATURDAYS AT THE PHILHARMONIC by Megan Staffel

Patsy Smith left Rochester, New York on a sunny Saturday morning intending to drive all the way to California. But after three and a half hours, crossing through an Indian reservation, she got lost. On a long, straight road, where there hadn’t been a route number for many miles, there was a sudden break in the forest and she saw a small building with cars and trucks parked in front. She turned in to ask directions.

Pulling the door open, she smelled beer. She saw men with their backs to her sitting at the end of a room on bar stools, and close by, a few small tables and chairs that were mostly empty. The door snapped shut behind her and in the sudden darkness all she could make out were the neon beer signs. She stood still, waiting until her eyes adjusted. It was nineteen sixty-eight. Patsy was sixteen. She had an old car, a hundred dollars, a pillow, a blanket, a pair of broken-in lace-up boots; that was the total of her possessions. But it was all she needed.

The man sitting at the table closest to her was the only one who had seen her come in. He stared at the girl with bare feet, filthy pants, long curly hair, and a wide pale face that even at that moment in a strange place, had an oddly quixotic expression.

Patsy was remembering a fact from seventh grade New York State history. These Indians, the Seneca, were called Keepers of the Western Door. They were protectors. Maybe that was why she had chosen the route that went through their reservation, and now, having lost it, maybe that was why she felt so confident standing in the smoky room.

The men at the bar, a row of dark backs with dark heads, talked quietly. When her eyes adjusted, she saw the man sitting by himself at the closest table. A shaft of light, coming from a small window, settled on his shoulders and made the rest of the room unimportant.

Patsy Smith stayed by the door, covered in shadow, but lit up, inside, by the beam of the lone drinker’s attention. She had left her home in a rush and on this first afternoon that she was on her own, she could already see that when she was away from her family, she, as a separate and independent person, would matter. The man in the light was slowly standing up. He didn’t look at her, but she knew she was the reason he’d gotten to his feet, and not the bathroom or some peppery old geezer sitting at the bar.

“Help you?” he asked.

It was not a friendly face. It was too hard for that. But he looked at her straight on, the raw flat angles of his cheeks glistening.

“Did I miss a turnoff or something? Route seventeen? I think I lost it.”

There was a flicker of amusement at the corners of his mouth and he said very slowly but in a proud tone, “You most certainly did. This is the beginning of the end of everything you could call familiar. So why not stay for awhile?”

Her warning system had been defused long ago. So it didn’t make her nervous to be the only woman in a room of stoop shouldered old men with a younger one who spoke in riddles; in fact, it sent an excited shiver down her spine. She joined him at his table and had a beer. And when he asked her a question, she told him a few things about herself: that she was going to California, that she had major plans, that she didn’t know exactly where in California, but that was only a detail. He told her about Handsome Lake.

“He’s the prophet who saved the Seneca from the white man. His visions restored our people.”

“Handsome Lake,” she repeated, her brain foggy from beer on an empty stomach. “That’s not your name, right, that’s someone else?”

“Someone else.”

“Well I’m Patsy Smith.” She extended her hand, aiming all of her enthusiasm into his dark, simmering eyes.

“Uly Jojockety.” He said it softly and without any salesmanship, but he did offer his hand, and when she took it, she could feel the dry grittiness of his palm and realized how far she was from the land where people with soft palms named Smith ruled over her.

“So who is this Handsome Lake? Does he have a Bible, sort of, or a radio program?”

He laughed. “No, this was long ago, 1799.”

“You’re kidding.” The way he’d spoken she’d thought it was now. “So…how do you know about him?”

“You see, we’re not like you. What we have is a straight line that goes from this day now to his first vision in 1799. The now, the here,” he touched the top of the table, “it rests on what happened before.”

“That’s really far out,” she said, thinking to herself that you might want to remember old Indians, but old white men it was probably better to forget.

Sometime later, she left him to go outside to pee. And while squatting behind the building, her ass visible to anyone who might walk past the row of trash cans, she was startled by a crackle of leaves and looked up. There he was, looming over her, his face more craggy from the ground up. Apparently, a lady’s bare squat didn’t prohibit a man’s gaze.

“No need to be embarrassed. Nothing new about a woman pissing.”

She pulled her jeans upwards, careless about what he might see, and he said, “but girls from Rochester, now I thought they only used toilets.”

She was stung by that word, girls. “Some maybe,” she answered, “not me. I’ve been doing this forever.”

She had her third beer leaning against the trunk of a cottonwood that was as ancient probably as the events he spoke of. He told her about the United States government stealing ten thousand acres of the most fertile Seneca land, river land that had been protected since 1794, in a treaty signed by General George Washington himself, how they’d removed his family and a thousand others. Just to build a dam that could have been built somewheres else. But no, Indian land was their choice. The good people of Pittsburgh, three hundred miles away, needed protection, by the US government, from the inconvenience of high waters in the spring.

“They burnt our house down, cut our trees, gave us a handful of dollars, and stuck us in a little white box with all the modern conveniences we didn’t want. They took it all. No more fish, no more fields, no more forests, no more longhouse. No wait,” he held up a finger, “let me be fair, they moved the longhouse. So then they said, what do you Indians have to gripe about? Okay? What do you Indians have to gripe about? And now do you know what they’re saying? They’re saying, wait and see, we’re going to lay route 17 right through your reservation and cut it in half. You saw how it stopped, right?”

“It just sort of disappeared,” she said. “And then all these little roads you were supposed to follow were really confusing and I got lost.”

“Exactly. That’s because we will not let a foreign government make a highway through our land.” With his hand on his chest, he intoned in a solemn voice, “I pledge allegiance to the Seneca Nation to frustrate the United States Traveler forever and ever.”

She laughed, happy to collude in such vehement anti-establishment feelings.

The sun was sinking. Rays of light were scattered by the leaves that laced the blueness of the afternoon. She knew she was drunk. But only partially was it alcohol. The rest of her euphoria was caused by the situation, the fact that her parents had no idea where she was, that she hadn’t had anything to eat since dinner the night before, and that a man with a kind voice and a long ribbon of hair, a man who was of people who had things worth remembering, was becoming her friend. Just then, his hair was brushing her arm, his full purple lips were parting slightly to ask, “How old are you Patsy Smith?”

“I’m old enough to know what you want. And I’ll tell you something, Handsome Lake, I want it too.” It came out just like that, one whole piece, smooth as something memorized. But she had never before said anything like it. She watched his face, gauging the effect, and then, with the same quiet authority the first violinist in the orchestra lifted the bow and laid it across the strings in preparation to begin the symphony, she raised her arm and set her long, pale-fingered hand on his blue jeaned thigh. Every Saturday of her entire life, her mother had gone to the Rochester Philharmonic. And so it was on that beautiful afternoon she was sitting in the audience, straight-backed and focused, as her daughter, who cared nothing for classical music, was sprawled on the ground a hundred and forty three miles south, orchestrating, with the same drama and promise, slender fingers on a stranger’s thigh.

But the Keeper of the Western Door leaned away. He sat back against the tree trunk and said, “There’s nothing special here. Nothing romantic. What we have is poor land and complicated weather. This is the place, Patsy Smith, where all hopes are destroyed, all expectations are lowered, and every vision of the future is worsened. I’m warning you. Anyone who survives crawls away injured. So do you really know what you’re doing? Because the only thing to recommend me is the before and the here, the this.” He put a lean hand on the ground underneath him. “But not the after. Clear on that?”

She loved the sound of his voice. She could just lie down and listen to that kind of poetry all her born days. Uly Jojockety was a teacher. He would teach her everything she needed to know. She removed her hand from his thigh, unzipped her jeans, and pulled them down, flinging them off with a heroic flourish. Oh, the terrible wrongs that had been done to him and his people!

But then, as his body moved over hers, cutting out the light, there was a moment that dropped out of the progression. She knew she would remember it. It was before anything happened, when she was still a girl from a suburb of Rochester escaping difficulties at home. And then, as those rough hands discovered her, she watched herself become someone else, someone she hadn’t met before, someone who was outspoken, a woman who would be comfortable in her life, who would feel for others. She’d say, sweetheart, honey, baby cakes, announcing her affection for whomever it was she spoke with. That person would take over. She would lead her from one sorry man on the earth to another, moving from Salamanca, New York to Olean, Batavia, Buffalo, always keeping to the clouded western side of the state until she’d had enough of other people’s troubles. The wisdom was hard-earned. And when she was in her fifties, having been through it all — children, booze, narcotics — her body would cease its raging.

But that was the future. It would take thirty-seven years to get there.

Listen to Megan Staffel’s reading of “Saturdays at the Philharmonic” below…

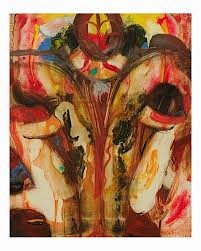

Megan Staffel explains that this untitled painting by Annabeth Marks feels connected to her story because it “expresses female sexual longing.”