ISSUE 31

POETRY

SOMETIMES, WHEN I TRY TO TYPE WORLD by Priscilla Wathington

WOMEN’S LIT by Anemone Beaulier

RETURNING TO PRAYER by Satya Dash

DOG GHAZAL by Zakiya Cowan

TWO POEMS by Timi Sanni

TWO POEMS by Kyle Okeke

STUNNED AWAKE by Karen Kevorkian

THE FOREIGN JOURNALIST DID NOT HAVE TO WRITE ANYTHING NEW by Ting Lin

AFTER THE THIRD SNOW DAY IN A ROW, I’M READY TO THROW THE TOWEL by Julia Kolchinsky

IN GEOMETRY CLASS, YOU LEARNED YOU COULD DRAW by Ian Cappelli

FICTION

SOUTH OATS by Joshua Jones Lofflin

BRATS by Irene Katz Connelly

LAST FACES, PAST FATHERS by Bri Gonzalez

CNF

I AM SORRY THAT I NEVER SAID GOODBYE by Pegah Ouji

- Published in All Issues, Issue 31

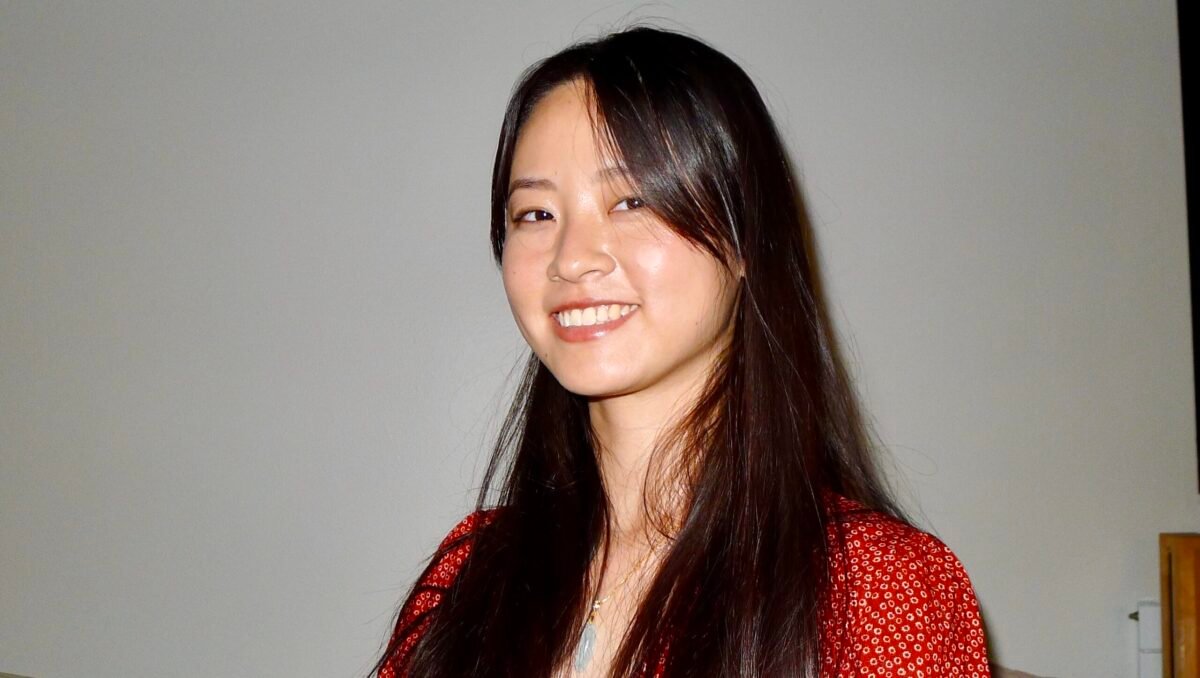

BRATS by Irene Katz Connelly

As a graduation present, Janie’s mother bought her a plane ticket to Budapest. “Not that I want to give my tourist dollars to those skinheads,” she said, referring to Hungarian society in general. “But someone needs to check on Eve.” She had not asked if Janie had other plans for the brief interval between receiving her diploma and starting her new life as a product manager, so the ticket felt less like a treat than an assignment: Janie was to convince her sister to leave Europe and find a job with benefits in the New York metro area. Over the phone, Janie chastised her mother briefly for treating her like a child. But she wasn’t busy, and she did have things to discuss with Eve.

Their mother believed that Eve was sharing a fin-de-siècle flat in the historic center of Pest with three French exchange students. She did not know about István, the actual Hungarian man in whose apartment Eve had apparently been living for several months. Neither did Janie, until Eve collected her from the airport and steered her toward a subway headed across the Danube to grubbier Buda. “We met at a reading,” she said in the loud and slightly languid voice that marked her, despite her best efforts, as having grown up in New Jersey. “He wants to improve his English so he can work abroad. I sent you some pictures of him, remember?”

“So none of us even have your real address?”

“You sound like Mom,” Eve said. “Do not tell her about this. And definitely not your father.” She said she would break the news when things got more serious. Janie asked what she meant. The train creaked into their stop and Eve busied herself dragging the suitcase onto the platform.

At the ticket kiosk, Eve explained that Janie could buy a week-long student pass that would save a lot of money.

“But I’m not a student anymore.” She showed Eve the conspicuous expiration date on her college ID.

“If someone comes on the train, you just flash it super quick. I use the student pass.” She was already negotiating with the machine, confidently parsing the Hungarian instructions until it spat out a hard, purple card.

Aboveground, Janie maneuvered her suitcase with difficulty over slanting slabs of pavement. They passed buildings of identical Soviet make, balconies overflowing with laundry and hardy plants. The uniformly blond pedestrians who paused to make way for the suitcase looked like they had done unspeakable things during World War II. Of course, most of them were no older than Eve. What Janie knew of Eastern Europe came from her grandparents, born in various towns that now existed under different names or not at all. In their infrequent stories, the weather and the food were always bad, and no road led anywhere good except the one that landed them among the synagogues and three-bedroom colonials outside Newark. Janie’s relatives were distressed when Eve returned to Hungary as an English teacher, and not just because she was far too old, at thirty, to be finding herself. In lowered voices, they asked: didn’t Eve feel strange, going back there? Their mother replied woefully that she certainly would.

They took turns carrying the suitcase up the four flights of stairs in Eve’s building. The landings sported gauzy portraits of the Virgin Mary and other, less identifiable saints, who gazed indifferently at them as they paused for breath. István, bearishly tall, opened the apartment door while Eve was still searching for her keys. He surprised Janie by kissing her on both cheeks.

“We are excited for you a long time.”

“Excited for you to come,” Eve amended. István’s body seemed to want to escape from the clothes that, at home, Janie and her friends—and especially Eve—would have derided as Eurotrash—knees bulging out of artfully torn jeans, chest hair teeming over his collar. But there was something potent to him, even in the careful way he arranged himself on the couch so as not to take up too much space. Janie could see why Eve was proud of him.

While István made coffee, Janie asked if she could connect to the WiFi. Eve said, “Can’t go an hour without talking to your girlfriend?”

“Exactly,” Janie said. Unaccustomed to traveling without Amy seeing her off, she had sent several texts and a rambling email before leaving home. On the plane, she bargained with herself, that if she kept her phone off until arriving at Eve’s, she would have a response waiting. But the messages remained unanswered, and not because her American phone wasn’t working; a text from her mother, reminding her to take pictures, had come through promptly.

Eve asked if there was anything special Janie wanted to do while she was in Budapest. Janie said, “People were telling me about the ruin bars.”

“Ruin bars.” Eve rolled her eyes. “I think we can spare you those.”

Instead, they took Janie to a shawarma place across from their building, where István had once gotten food poisoning. Janie’s jet-lagged body longed for her familiar dorm, the incense Amy burned. She found it difficult to be hungry. Eve requested all the toppings on her pita and ticked off the things Janie should see during the day while she and István worked: the National History Museum, the parks. When István mentioned the Holocaust memorial on the Danube, Eve countered that it was incredibly dreary. She and Janie, as Jews, should be exempt from visiting.

“It is a very important work,” István said seriously. He explained to Janie that the monument consisted of dozens of bronze shoes arranged as if they had been scattered on the riverbank. “The shoes represent the lost children.”

“We know,” said Eve. They had studied the monument, sandwiched between others in interminable PowerPoints, at Hebrew school. She turned to Janie. “Why didn’t you want to bring Amy with you? It would be better if you had someone around for the tourist stuff.”

Janie said Amy had things going on.

“What happened, she got a job out of state? Are you breaking up?”

“We’re not breaking up.” Janie made a face to indicate that she wanted to talk about it later, without István.

Eve failed to interpret the face. “Amy and Janie,” she said, sing-song. She liked to quote from the cheerful, earnest book reviews Amy posted on Instagram and to mockingly repeat the mantra on Amy’s favorite tote bag, that a well-read woman was a dangerous creature.

Perceiving the need to change the subject, István pointed outside, where the owner of the restaurant was placing a dish of scraps out for the street cats. “He should not do that,” István said. “Already this year, they are having cases of rabies.”

“He’s always worried,” Eve said sagely. “I don’t even have to read the news, because he tells me everything bad that’s happening.”

“It’s because they are foreign,” István said, still looking outside. “Should I tell them?” Eve reached for the pickles. “Tell them that they’re foreign? I think they know.”

István appeared confused and opened his mouth as if to clarify. Then he realized that Eve was making a joke, and his face softened and he laughed and reached for her hand.

*

Janie covered attractions efficiently during her days alone. Instructed by a guidebook kept hidden from Eve, she ate goulash and strudel and bread filled with poppy seeds. She went to the Holocaust memorial and sent a picture to her mother, who responded immediately: How awful. She went to the expensive baths and the inexpensive baths, and wrote Amy an email in which she tried to capture the Ottoman grandeur of the pools, the Communist-era cafeteria, and the pile of construction debris in the middle of the women’s locker room, to which no one paid attention.

Each night, Eve made plans to go out with more friends than Janie had ever known her to possess: the abandoned roommates, customers of English-language bookstores, sturdy former classmates of István’s to whom, she advised, Janie should say nothing about having a girlfriend. Eve liked to sequester her friends for confidential gossip, her relentless questions allowing the interlocutors to unburden themselves. Janie wanted this for herself, the relief of being emptied of her secrets, which were more important than those of the roommates.

But Eve was not in the mood to provide this service to her. In the apartment, she retreated with István to their alcove bedroom. They had taped a sheet over the doorway—“for your privacy,” István said—as if that would prevent her from hearing them have sex. István said things to Eve in Hungarian, his voice thicker and older than when he spoke to Janie in English.

*

When the weekend arrived, they went to Visegrád, where there was a castle. As the train moved away from Budapest, the houses lining the tracks grew smaller and shabbier. Billboards endorsing right-wing politicians loomed close and disappeared as István translated the slogans. Eve, hunting in her bag for lipstick, tossed her passport and a handful of old receipts onto an empty seat. Janie picked up the passport before it slid onto the floor.

“That is a good passport,” István said, tapping the imperial red cover. “She can work anywhere in Europe, unless they do the Brexit. Do you have one?”

Janie shook her head. When they were children, Eve sometimes opened the sober desk drawer that contained their passports and laid them before Janie like playing cards: four blue ones and the fifth which she alone possessed, as a British citizen through her father. The red passport, she explained to Janie, entitled her to certain privileges. She could get a job in London when she grew up and stay there as long as she wanted. Moreover, if the Holocaust repeated itself in America, which they had been told was a definite possibility, she would have a place to go. Her innocuous English surname would allow her to cross the border. Janie’s, Klein, would certainly bring trouble.

Even on the train, Janie could easily picture the sunlight filtering through the sycamores outside and landing in golden splashes on the documents. She could not picture, at the time, anything worse than Eve traveling without her indefinitely.

At the last stop before theirs, a transit worker in a purple vest boarded and worked his way up the aisle, checking tickets. Eve produced her battered college ID. “Hold it like this,” she said. “With your thumb over the date.”

The transit worker barely looked at István or Eve. But he lingered over Janie, who proffered her ID tentatively and at an awkward angle. Janie wondered what would happen if she were apprehended for using the reduced fare pass. István looked at the card casually and said something in Hungarian that made the transit worker laugh. When he moved on, Janie asked him to translate.

“I said that you made a mistake because Americans don’t know how to use trains.” He spoke sternly, although surely he knew that the reduced-fare pass was Eve’s idea.

“Good thing we have men around to sort things out,” Eve said serenely. “Shit. What did I do with my passport?”

“I have it,” Janie said.

Eve snatched the red file. “Oh come on,” she said. “Don’t act like you have to take care of me.”

Janie said she wasn’t acting like that.

“I wouldn’t have lost it,” Eve said.

*

The French former roommates all studied business and accounting. Through events hosted for international students, they had acquired various pseudo-boyfriends, also studying business and accounting. Traveling into Pest to meet them (at a ruin bar, because the roommates loved them), Eve seemed especially satisfied with herself. Some of the roommates were younger than her, some of them thinner and prettier. All of them would have enjoyed living in sin with a grown man, a man who didn’t complain about his master’s program because he had a job. Only Eve had pulled that off.

With the roommates competing to appear clever and fun, Janie noticed how fixedly István gazed at Eve, and how reluctantly he turned to anyone else. In the warmth of his regard, Eve seemed to unfurl, her hair gaining luster and her lips growing pinker. Janie wondered if she herself had ever appeared this beautiful when she caught Amy looking at her across a party. Although they had been dating for three years, veterans compared to their friends, that still sometimes happened. Janie decided she was going to force Eve to talk to her, even if she had to do it in a ruin bar. As she settled on this decision, the loudest roommate, Camille, produced a baggie of cocaine. Eve clapped her hands like a child presented with cake. Everyone took turns going to the bathroom except Janie and István, who said he didn’t like his thinking to be interrupted.

Eve asked, “What important things are you thinking about right now?” A pseudo-boyfriend, Phillipe, laughed. István explained stiffly that it wasn’t about the particular moment but the way he lived his life in general. Sensing that he was offended, Eve bent over his chair to kiss his forehead, letting her loose sweater hang open in front of his face. Unlike Janie, she had heavy, serious breasts, breasts which demanded underwire bras with many hooks. Their mother said that Janie should urge Eve to take up Pilates, which would make things easier for her in the long run. Had their mother been at the bar, she would have been forced to recognize the power Eve’s body could exert, for István was smiling shyly up at her breasts. When it was Eve’s turn in the bathroom, he observed to Janie that they were very close for half-sisters.

“I really just think of her as my sister.”

“Oh.” Istvan nodded. “Yes, of course.”

“Is that how Eve talks about us? Half-sisters?”

“Well, I don’t know.” He sipped his beer carefully. “It is hard living with a stepfather, no?”

Janie said that Eve had been living with Janie’s father since she was eight.

“I’m sure he is very nice,” István said. “I have stepmother too. It is maybe different with women.”

Janie asked István if he had any siblings and he said four, two younger sisters and then another set of girls that were his father’s by his second wife. Divorce carried a significant stigma in Hungary, so his mother had been very much alone as she raised them. From a young age, István had found himself the man of the family, navigating environments with which neither of his parents had any experience, like the university system, and providing guidance to the older girls. Both of them were studying to be doctors, and although István saw his father on holidays, they refused to come along; they found it too hard to see those other girls, who had only ever lived with two parents.

“I’m sorry,” Janie said. She was embarrassed that Eve had complained about their perfectly functional family to a man with real problems.

István shook his head. His eyes flicked to the bartender, who was marching grimly towards the bathroom. “We are going to be ejected,” he said, getting up to settle the bill. “Do you have any cash?”

Janie gave him all the forints in her wallet. While he waited at the bar, Eve emerged from the bathroom and draped herself over his shoulder. Although he was still shaking his head, he slid a hand under her sweater to rest on her bare back. Already Janie missed being touched in public like that.

After the ejection, Camille hesitantly suggested moving to an acclaimed strip club which was unknown to most foreigners. The club was located underground, in a former bunker of Cold War significance. The men appeared studiously indifferent. Probably it was their idea.

“It’s not the trashy kind,” Phillipe assured Janie. “It’s more like performance art. Right, István?”

Grudgingly acknowledging that he had heard of the club, István said it would be hard to get there. “It is in completely different neighborhood.”

“I don’t mind a little walk,” said Eve, who, not having to worry about maintaining her grip on a pseudo-boyfriend, could contemplate the idea in perfect good cheer. She linked arms with Janie for the first time. It felt like an opportunity.

Camille led the way resolutely. Philippe, addressing István like a grandfather in decline, asked questions about the neighborhood’s history. Janie slowed her steps until she could hardly hear. Eve asked if she was tired.

“No,” Janie said. “I have to talk to you.”

“Janie, we’re out. We’re about to be in a literal strip club.”

Janie said they were always out.

“Yes, because I’m trying to show you the city where I live.” She let out a breath. “What is it? I know you haven’t been talking to Amy.”

Already the conversation was deviating from Janie’s vision. She thought she could shock Eve into sympathy, but her sister had already intuited the problem and failed to display even the nosy interest she extended to her friends. Still, Janie could not prevent herself from confirming that yes, the problem was Amy. Nor could she pause to wonder why, despite years of experience with Eve, she had imagined such a different scene. She had come to her sister for help and the words were already climbing out of her dry throat, into her mouth.

*

A month earlier their parents had hosted a graduation party, ostensibly in Janie’s honor but really for their own friends. No matter what Eve was doing with her life, they had successfully dragged one daughter from the swamp of adolescence to the firmer terrain of employed adulthood. Amy and Janie spent the afternoon scooping ice into the crystal buckets Janie’s mother had received on the occasion of her first marriage and pragmatically declined to discard. They didn’t mind; earlier, they had been looking on Facebook for one-bedroom sublets.

When the wine supply was dwindling towards the end, Janie’s father asked Amy to help him bring more bottles from the cellar. (“This part, obviously, I wasn’t there,” Janie said. “I’m just telling you what she told me.” Eve lit a cigarette.) He opened the refrigerator that kept the reds at the correct temperature and asked absently, in the manner of making small talk, if she had only ever dated women.

“Yes,” said Amy. She was wedged between the washing machine and the open door of the refrigerator. Though she was startled, she knew that Janie’s parents were prone to making comments, and she reminded herself that they had always been kind to her.

“Not like Janie,” he said, reaching around the door to put one and then two and three bottles into Amy’s arms. “She always had boyfriends in high school.”

Amy wondered if she could somehow maneuver herself out from behind the fridge, but that would involve either squeezing by Janie’s father or telling him explicitly to move away from her, which seemed dramatic. He took three more bottles out of the fridge and closed the door clumsily. Amy decided he was tipsy.

“After you,” said Janie’s father. Amy preceded him up the stairs. Midway up, something that felt like a hand grazed her back pocket. Amy stopped. The bottles in her arms clinked.

“Can you see?” he asked. He spoke so casually that Amy decided she must have been mistaken. But as soon as she resumed climbing it happened again, something skimming across her jeans. Amy stumbled. Janie’s father said, “Let me get the flashlight on my phone.”

“That’s okay.” Amy had done bystander intervention training and attended campus speak- outs on sexual harassment, but her learning now seemed abstract. She couldn’t remember what she was supposed to do. On the other side of the basement door, she heard the jangle of women’s voices. She breached the door and stumbled into the sudden brightness, blinking as the light dissolved the man who had perhaps pursued her up the stairs and reassembled him into the innocuous parent she knew.

“And then what?” said Eve.

“I mean, nothing.” The party wound down and Janie, believing that Amy was tired, reminded her that she could rest upstairs. But Amy didn’t rest. She replayed the afternoon’s events, shaping them into a story. She waited until later that night, when they were alone in the bed which—since they couldn’t get each other pregnant—Janie’s mother happily let them share. Only then did Amy reveal what she believed had happened.

“But what did Mom say?” Eve flicked her cigarette, launching the ash away from her boots with casual accuracy. She still did not seem shocked.

Janie felt that Eve wasn’t processing the situation. But neither had she, at first.

“I didn’t say anything to her.”

Eve raised her eyebrows.

“She didn’t know if it really felt like a hand. And he was acting completely normal. He would have to be—he would have to be a completely different person.”

Eve continued to say nothing, which was not her usual style. The silence prodded Janie forward, forcing her to admit that she had promised to have a conversation with her father, just to clear things up, but that she had not actually done so and that as a result Amy was no longer speaking to her.

“Oh.” Eve arrived at the filter, which she crushed under her heel. “I get it.”

“What do you get?”

“You want me to say you did the right thing.”

Automatically, Janie said that was not what she wanted.

“I mean, it’s not that I love Amy so much—”

“What a surprise.”

“But I didn’t foresee you getting dumped because your father’s a lech. And I really didn’t foresee you spilling your fucking guts to me because you think I’m going to be okay with it.”

“Don’t fucking talk about him like that.” The swear squeaked out, reminding her infuriatingly of her childhood: whatever Eve did, she would do, too. They had grown up eating at the same table, enjoying the same privileges. Only in Eve’s absence did Janie’s father occasionally complain that he’d paid her entire college tuition and got no credit. And yet Eve had always acted like she could simply remove herself from the family through the power of her own scorn.

“Janie, he hits on everyone.”

Janie said that he did not.

“You know what Mom said to me once? We were at his literal birthday party, and he was falling all over that woman—who’s the one from business school who keeps horses?”

“Marianne.”

“Yeah, Marianne. Anyway, he was practically looking down her shirt, it was so obvious Mom couldn’t ignore it, and she just shrugged and said, I married a charming man.”

Eve didn’t just think she could remove herself, Janie realized. With very little effort, Eve could marry István, wriggle out of holidays, and ask after your father on the phone.

“So,” Eve prompted, not completely unkindly. “What’s the situation now?”

“I don’t know. We really need to find an apartment this month.”

“She’s breaking up with you?”

“She’s not breaking up. She’s just not talking to me at the moment.”

“I would break up with you, if I was her,” Eve said.

*

When they caught up with the others, the roommates were huddled by the steps leading down to the club, shuffling out their IDs.

“Men only,” said one of the bouncers, shaking his head.

Camille laughed. “Seriously?

“The girls don’t like it. Men only.”

“Fine.” Annoyed but not seriously so, Camille turned to leave. The boyfriends did not follow. They were conferring, and through Phillipe they announced that they were going to go in—just for a little while, to see what it was like.

“You’re actually going without us?” Camille said. Phillipe mouthed something unintelligible. “Guys, that’s gross.”

“I am not going,” István said. Camille didn’t appear to care.

“Okay,” said Eve, addressing the bouncer. “What about the men and me?”

“Men and you,” said the bouncer, considering. The cold air had made Eve’s face paler and her pink cheeks more striking. Her black hair, blown out earlier, was just beginning to curl. When Eve looked so messily beautiful, Janie could hardly believe they were related.

“I won’t cause any trouble,” she said, clasping her hands meekly. “You’ll hardly know I’m there.”

“What the fuck,” Camille said. The bouncer hesitated. Then he waved Eve in.

Outside, in the unknown neighborhood, the remaining women were dependent on István, who led them to a bar that was authentic in the wrong way. If the night was to be salvaged and the pseudo-boyfriends faced in the morning, the episode needed to be laundered into a fun anecdote. No one seemed capable of the verbal effort.

István said, “Eve is safe. They don’t like women because they come just to look. They don’t want to pay.” Janie realized her mouth must be set in the same fixed way as Camille’s. She was not worried about Eve’s safety. She raised her eyebrows at István, causing him a moment of visible panic. He said, “Most women.”

Janie announced that she was going home.

“Now?” István glanced toward the club, toward Eve. “How will you find the way?”

“I have data,” Janie lied. She didn’t know where the tram was, and she wished that István would offer to take her. But he knew Eve well, knew that she would want him to wait for her, at anyone’s expense.

On the tram, there was only one shaggy man sleeping and two old women whose stiff postures expressed chagrin at having to resort to public transit so late. Janie sprawled across two seats. She opened her camera roll and flicked through her recent photos, which seemed studied and tense. She looked through her texts with Amy and her texts with Eve and her spam emails. She wished she had data. She wished she could stop feeling bad for herself. She wished she could tell Eve she was being a total cunt, to use the word as their mother occasionally did, without any feminist misgivings diluting her tone.

Just over the river, at the stop by the Széchenyi Baths, a transit worker boarded the tram.

Watching him chat with the old ladies, Janie felt entrapped. She extracted her student ID and practiced the nonchalant placement of her thumb over the expiration date.

When the transit worker finally reached her, he snatched the ID from her hand so quickly she couldn’t even consider tugging it back. Shaking his head, he said something reproving in Hungarian.

“I’m really sorry. I only speak English.”

“You are not student,” the transit worker said, widening his stance as the tram hit a bump.

Janie jostled in her seat.

“I am a student,” she said slowly. “That date is when they gave me the ID.”

“No,” said the worker. “No, no. Pay fine.”

“I don’t want to pay a fine.” Indignation came so easily that Janie almost forgot she was lying. “I’m a student.”

“Not valid,” said the transit worker, closing his hand around the card. “Pay fine.”

“I’m not going to pay a fine,” Janie said, summoning the contemptuous voice her father used when a flight was canceled and he wanted the maximum number of points. She would run off the train at the next stop.

“Okay.” He shrugged agreeably. “I call police. We arrest.” He called out to the tram driver, who immediately slowed. One of the old women turned and made a displeased clucking noise, looking not at the transit worker but at Janie.

“Ten thousand forint,” said the transit worker. About thirty dollars. Janie opened her wallet and remembered she had given her cash to István.

“I don’t have ten thousand,” she said triumphantly, taking out the loose change from the bottom of her wallet. He was hardly going to follow her to an ATM.

“Dollars,” said the transit worker, pointing at the wallet. Janie looked down and saw she had inadvertently revealed the sheaf of American bills her father had handed her at the airport.

“Fine.” She withdrew forty dollars, which would more than cover the fine. The transit worker folded them messily into his pocket but kept his hand outstretched. He was demanding a bribe. She glanced at the tram door and the transit worker shifted so that he blocked it. The other passengers, who surely could see what was happening, appeared not surprised or outraged but merely bored. The transit worker beckoned with his hand.

Janie handed over two more twenties and tried to close her wallet, but the worker knew there was more and remained politely but implacably blocking the door. Janie’s father always gave her money when she traveled alone, delivering a stack of twenties with a lecture on the importance of carrying cash. From the uniform crispness of the bills, which she could feel as she handed them one by one to the transit worker, she knew that her father got them directly from the bank. Only when her wallet was empty did the transit worker call out to the driver, who opened the door.

“This isn’t my stop,” Janie said.

“Buy new pass,” the transit worker said, tucking the dollars into his purple vest. “Goodnight.”

Janie stepped unsteadily from the tram. One of the women rose heavily and followed her, assisted on the step by the transit worker. The tram heaved off. In its absence, only the Gothic sconces outside the baths offered weak light.

Janie fished for her phone before remembering she had no data. She would have to follow the tracks until she saw Eve’s street. The old woman walked confidently in the other direction. As she passed Janie, she veered unnecessarily close and murmured, “Slut.” Her handbag, leather and substantial, slapped against Janie’s elbow. Janie looked down at her jeans and wrinkled T-shirt. It must have been the best, most potent English word the woman could summon.

*

She did not expect to find her sister sitting on the building’s dirty steps, intermittently illuminated by the motion-sensing light. Eve was eating a biscuit, the kind that came individually wrapped with cappuccinos. Briefly, Janie imagined Eve chastising István for allowing her sister to leave alone, hailing a cab to drive up and down nearby streets, searching.

“Were you looking for me?”

But no, Eve was equally surprised to see her. She had gotten bored with the boys, who acted like meatheads in the strip club, and only realized after wandering home that she was missing her key. Eve brushed crumbs off her coat, and a street cat materialized instantly to collect them. “Why are you all by yourself?”

“What was I supposed to do?” Janie pointed out that she had been abandoned.

“Not everything is about you.” Eve had needed to escape István and his ceaseless instructions. It was her own fault, she admitted, because she used to think it was cute when he told her what to do. She spoke unhurriedly, as if Janie had asked for a comprehensive account of her problems. The cat ventured forward and Eve put out a hand. Janie stomped her foot, sending him skittering out of the light.

“They have diseases,” Janie said.

Eve said that maybe Janie ought to date István. Janie said that he certainly deserved a nicer girlfriend, the way Eve walked all over him.

“Honestly, you’re being a huge brat,” Janie said. “I came here to talk to you.”

“Oh, I’m the brat? I’m a bad girlfriend? Amy got groped by—” Eve didn’t say who had groped Amy. The cat returned, ignoring them in the search for remaining crumbs. “She was harassed in our own house. And you’re mad at me because I’m telling you that if you want her to stay with you, you have to do something about it.”

Eve was not listening, Janie said. She was trying to explain that Amy had come to believe an impossible thing.

Having exhausted the offering, the cat rubbed its head along Eve’s ankle. Eve brushed its head, then crumbled the remainder of the biscuit and extended her hand. “So you had to talk to me because nothing happened.”

Janie felt that she was being deliberately misunderstood, but she couldn’t say exactly how.

“Seriously.” The cat nosed around Eve’s hand. Eve looked at Janie. “Did you really come here to tell me nothing happened?”

Janie began to speak, to say she didn’t know what. Then Eve snatched her hand from the cat. “Did it bite you?”

“Just a little nip,” Eve said. “It didn’t break the skin.”

“They literally have rabies.” Janie sat down and examined Eve’s forearm, seeded like her own with ineradicable dark hairs. No scratch was visible yet, but she thought they should go to the hospital.

Eve said that István had made her paranoid, that people sat in cafés with street cats in their laps. She said, “I thought you wanted to talk. Now we’re talking.”

“I do want to talk, but you’re—”

“There is no way Amy will stay with you if you don’t listen to her.”

Janie put down her sister’s arm. She had hoped to be understood by the lazy, prurient Eve, not the sister who now fixed her with a dissecting regard, who was willing to remake her own life, to strike out again and again, when her expectations were not met. Even had she been disposed to, Eve couldn’t deliver the comfort Janie wanted, only guide her toward that free and lonely territory where she lived, ungoverned. Janie did not want to join her there. She didn’t want to think about a future without Amy, but she already knew how it might unfold. Soon, she would be arranging first dates at bars with four or more stars on Google Reviews.

“What am I supposed to do?” Janie said. “They’re my parents.”

Eve looked away and put an arm around Janie, an uncomfortable pose familiar mostly from photos. “They are your parents.”

They sat quietly in the concrete night. Eve’s phone vibrated. She conceded that Janie should call István regarding their whereabouts and possibly the cat bite.

In the coming weeks and months, Janie would try not to remember the night too well. Her mind recoiled from her own insufficiency, what Eve only barely refrained from calling cowardice, until only fragments of the conversation remained. Eventually the trip receded into the ocean of things she had forgotten, breaching her thoughts only occasionally while she flirted with a woman who knew nothing of Amy, or when she sat on the subway, staring at a stranger’s shoes. In these instances, although she knew the moment only accrued significance in hindsight, Janie recalled that when she pulled up his contact that night on the steps (no surname, just István, Budapest), she saw the future piling up before her. The phone rang, the foreign pattern of trills and silences drawing her into the future, and she felt she had already watched Eve tire of István and return home. She’d helped their mother rustle up a job for Eve. She had become familiar with the kind of arrogant, striving man her sister perversely favored in New York, and assured her own more suitable girlfriends that they would come to love her sister. She’d weathered the lapses in communication that could mushroom into months for no reason at all, and coaxed Eve into anchoring one corner of the chuppah at her wedding. She’d called after her father’s cancer diagnosis, demanded and received Eve’s help shuttling him between specialists. She’d suppressed the urge to ask for any more explicit reassurance, and Eve never offered.

The phone stopped ringing and the motion-sensing light switched off, drenching them in darkness. Jane heard a cough, and István announced himself on the other end of the line.

- Published in Issue 31

LAST FACES, PAST FATHERS by Bri Gonzalez

after K-Ming Chang’s “Footnotes on a Love Story”

The greatest day of his life isn’t when his son is born. It isn’t when he learns he’ll be a father (for many hubris-heavy years, he thought he’d never* be one). The greatest moment isn’t his wedding, after he fell for his wife so deeply, surprising himself. Or the proud glint in both his mothers’ eyes** when he tells them—we’re expecting. We’re having a baby boy. Not the first time his wife says I love you, hands draped around his neck like a shawl, laced with wafts of lemon and paint thinner. It isn’t the time she kisses the bases of his palms*** as a boon. The greatest moment—after forty years’ worth of moments—is nothing remarkable. Partial clouds dilute sunrise. Eggs for breakfast. Scrambled but slightly runny, like residue rain slipping off a hot roof. His wife kisses his forehead the way a feather escapes a bird midair. His son, almost six, trips on himself and hits the floor like whump. His son doesn’t cry. Laying beneath the kitchen window, the kid absorbs daylight and spews it out**** with something like a pained laugh. His son stands, wobbles over, sits on his lap, and offers a crumpled piece of paper, bent in his fall. Indecipherable. Crayoned to the high heavens. Misspellings (or retellings) of his, his mother’s, and his father’s names. A note that he—the father—can’t understand but still tries***** to parse. Best. True. True? What. I. Happy. Or hurry. His son gifts it before stumbling away wordlessly. In the evening, around a dining table embroidered with loose bills and toy horses and pamphlets, his giggling son putting on voices only a child could master. His wife, brushing her husband’s hair to the side, leaves something tender at the bottom of his neck. Storm clouds roll in during dessert. He thinks, this, this is all I****** need. He dreams, and the dreams pluck light-poisoned eyes from his wife and son, who blink and laugh, disembodied.

*DISCLAIMER: Many nevers orbit his life until she picks them, one by one, and squashes them like errant bugs or a well-grown grape. She says, when asked why him—no, seriously, why him?—that she has the mundane ability to read marionette lines. Can translate who someone wants to be from two facial folds. And maybe she liked his best: shadowy, weak, but willful. He wasn’t meant to do what he did (leave her), not based on her predictions (the marionette lines), but it happened. Sometimes she thinks she must’ve willfully mistranslated him—other times, she accepts that she never saw it coming, that he’d taken her never and replaced it with a stained facsimile of himself. His side of the closet—all dust or hope—is gradually replaced with collections of oracle cards and books on beet farming.

**DISCLAIMER: When his mothers find out, news delivered by text from the woman who they know as their daughter-in-law (who writes I’m sorry and we’re still family), they say nothing. Over dinner, open iMessage as the centerpiece, his mothers remember the time he tried to glue his ears—protrusions he said were bulbous and ugly—to the side of his head so they wouldn’t stick out. Angles like catty-corners, then gone.

***DISCLAIMER: His hands on the table. His hands over his face, wet beneath, down his chin. His hands on the front door, magnetized, swinging it closed. His gentle hands on her gentle shoulders, phantom squeeze, a form of begging. Another chance for his hands to hold his child. The real reason he’s not home—his hands searching for some metaphysical truth, something she doesn’t understand, no matter how often he gesticulates through one explanation into the next. His hands illustrating the phrase find the truth of me and my body, which she thinks means he’s searching for a purpose he already has. He once told her he’s not sure what else he’s meant to exist for. Never clarified if he was talking about his belief, her, or a secret third thing, steepled in his fingers.

****DISCLAIMER: Her husband isn’t built for initiative but strives for it anyway. It’s too hot and blinding—a thing he doesn’t have the capacity for. Which is fine to everyone but him. Honey, she says. There’s no shame in taking care of yourself. Isn’t that your whole religious dogma thing—y’know, that thing you’re giving me up for?

*****DISCLAIMER: Some months, when he’s really gone, in a way that somehow supersedes the weight of their divorce documents—when it’s just her and their son for more miles than she can count, she wonders why this journey of his exceeds family. He calls it an inner test of growth or enlightenment. She calls it a cult. Wellness culture under some spiritual or religious veil she can’t parse. But he needs to grow his sense of self. She doesn’t know how he found the organization—or if they found him. Her son is eight now. He won’t talk about how he feels. She won’t much either. In bed, she recounts how the father of her child attempted to hand-build a crib and changing table and baby bookshelf without ever having wood-worked.

******DISCLAIMER: On the day he leaves, his son is mesmerized by his movements. Dad bending down to pat his head and hug him. Dad picking up bags he’s never seen unearthed from the closet before—leather, strapped to Dad’s back, bulging at the sides. The boy vaguely remembers hiding an action figure in the side pocket, left during a very important spy mission involving traitors and giant lasers and a T-Rex. Dad and Mom won’t look at each other but he’s not stupid—he’s right there—and can spot the potential collisions, both glancing toward the other but missing. The son, clutching a half-complete paper airplane, watches his father cry. And walk out the front door. For a while, he follows his dad down the road into town, but Mom catches up and takes him home.

- Published in Issue 31

I AM SORRY THAT I NEVER SAID GOODBYE by Pegah Ouji

I was helping my roommates, hanging up a pumpkin balloon for Halloween, when I got your text message saying you were in town. This was my first American Halloween away from my parents, far from Farsi, a world of English consonants, sour cream and meatloaf. I started typing in English, inviting you to the party, but immediately deleted it, retyped it in Farsi because I was always puzzled by English. How do you throw a party? Does it have corners you can grip? Where is it to be thrown?

You answered in English, Cool, I’m down.

I didn’t tell you but your black overcoat reminded me of the Mantou we wore in fear of the Morality Police in Iran. When I hugged you at the door, your eyes held the same distant look as if you were always looking above us all, into some galaxy where a new star was being born.

You didn’t want to dance so we sat in a corner on the gray shaggy carpet that always felt moist. I had asked you about life in LA, you had shrugged and said something I couldn’t hear in the hubbub of the music and the shuffling bodies, couldn’t even read your lips in that dimly lit room.

It was all too much; the loud music, sweating bodies stuffed in costumed- witches, superwomen, batmen- swaying to American songs I had never heard before, beats that didn’t move my body like a song of Andi could.

After whispering in your ears, I will be right back, I left the living room and retreated to my bedroom downstairs in the basement. I felt that just a few minutes of lying down on my cool bedroom carpet was all I needed as a recharge before I could subject my senses to the sensory assault again. To be honest, I was also overwhelmed to see you again, after all these years. We had parted as children, our last hugs exchanged in Tehran and now here, adults in a strange land.

Our families used to go camping in the wilderness around Shiraz. Remember the time we sat close, holding hands, sweat glistening our laced palms as we watched that mother goat give birth to her baby? Remember the slick, wet skin of the baby, as its mother licked it a few times, that shake of its hind legs as it tried to stand, and fell, over and over. Remember the newness of life, the fresh scent of a mammal’s first milk?

Walking back up the stairs, I resolved myself to ask if you wanted to leave the party, go for a walk around the block. But you were already gone, disappearing like the thin smoke of your father’s old motorcycle exhaust.

I am sorry I never said goodbye.

Now that you are gone forever, our friendship feels unfinished, a run-on sentence that will never benefit from the peace of a period.

For days after hearing the news, I tried to close my eyes, recall back that evening, and reconstruct the movement of your lips. What had you said when I asked, “How do you find LA?” “It’s alright. But I miss Iran. Or “It’s fantastic, I never want to go back to Iran.” Whatever the case, I knew you had said the name of our country, which also happened to be the name of your grandmother and perhaps you were just telling me about her and nothing more.

Now I will never know what thoughts went through your mind at those late hours of the night when the demons we bury in the day rise again restless, when we become porous, thoughts wiggling through like starving worms. Words. I would never hear slip out of your mouth again.

During our camping trips to Iran, words were all we exchanged, planning our futures, our Iranian husbands, you were going to become a pediatrician, saving lives of little ones. I wanted to become a chef, to cook meals that melted in mouths, that bound hearts. What does immigration do to us when someone like you, brown eyes brimming with the promise of tomorrows, turns into a twenty-year-old girl who takes her own life? There is English again, exasperating my confusion. What does it mean to take a life? Where is it taken to? If it is taken somewhere, can it be brought back? In Farsi, the news of your passing would be just that, passing, dying, unadorned, ugly, harsh, cold, moist carpet, a mother goat licking its placenta after the pangs of birth.

I checked on your mom’s Facebook page every day for two months, where every day she posted a photo of you, sometimes the same ones, you always smiling, words arrested in your mouth, your long hair draped over your shoulders, your eyes always looking off from the camera. Were you really beholding a realm beyond ours? Because when I think of you, my demons resurrect, it’s dark in my mind, and we are back at the party, crunching on popcorn and Oreos, and I am always asking you, how are you? And I am always staying put, never leaving, listening, hanging on to every word escaping your lips as if it were the last word I would ever hear from you.

In my mind, you’re always alive, and I’m a baker, serving you the sweetest saffron cake, both of us watching, from the branches of a mango tree, that baby goat taking its first wobbly steps into a new life, full of possibilities.

- Published in Issue 31

SOUTH OATS by Joshua Jones Lofflin

Before she divorced me, Layla ran the South Oats Sea Camp. Technically, I ran it with her though I only oversaw the ropes courses, checking the equipment for cracked helmets and fraying lines. The salt water did a number on them, was slowly eating away the entire camp, and we’d long since burned through Layla’s insurance payout. Soon, we’d have to let go of the college-kid counselors who always smelled of wet hemp and patchouli and unwashed hair. Layla said I coddled them. She accused me of ogling the one with a blue-green pixie cut and acned neck. You think she’s pretty because she wears those ripped short shorts, she said. You think she has a smackable ass.

That night, after she put her leg away, I tried to smack Layla’s ass. She only laughed at me, and I wasn’t even naked. Then she had me rub lotion on her stump, to moisturize the scars where the knee ended in a stapled flap of flesh. I made small motions with the flat of my palm until her jaw relaxed into a smile, and it was almost like before, back when South Oats was new, back when Layla let me touch the rest of her.

I traced the lines of her scars, their soft spidery ridges, and she sighed. When I ran my hands higher, she batted them away and called me pathetic.

*

Layla kept her prosthetic in a locked cedar chest at the end of the bed along with pitons, carabiners, a climbing harness she hadn’t used in years, old photo albums of our first summer of campers and how happy and fresh everyone looked then, and all of South Oats’ financial statements, now mostly bills or notices of lapsed payments. The leg lay nestled atop it all on a small bed of ropes. Sometimes I dreamed it escaped. Once, I dreamed it was choking me, had somehow grown a hand onto its plastic ankle, a hand with long fingers and neon-blue nails. Layla called the leg Marie, said I needed to stop staring at Marie so much. The counselor with the fluorescent hair was called Marie also. You want to fuck Marie, don’t you, Layla said. I wasn’t sure which one she meant.

*

Layla once caught me fondling Marie—the leg, that is. I’d snuck the key from her fanny pack and slotted it into the brass lock with hardly any click at all, but then her bedside light flicked on and she saw me holding it, my fingers running along the seam of its molded plastic. I tried to tell her I just wanted to check the financials, but she didn’t believe me. She finally rolled over and turned out her lamp leaving me still holding the leg. It gleamed in the moonlight and smelled of lavender lotion and soap. Marie the counselor’s legs were filthy and covered in dark, coarse hair—or maybe sand, it was hard to say. Everything at South Oats was coated in mud and sand. It’s on its last legs, Layla liked to say. She liked making leg jokes.

*

Marie the counselor worked the challenge course beneath the cliffs, clapping and cheering on awkward tweens as they struggled not to fall. Layla shouted at them to show some hustle, to show some teamwork, said she could do the course one-legged, and then she did, unstrapping her leg and passing it to Marie. She hopped onto the ropes without safety harness or helmet and worked her way upward until she was ten feet off the sand. Below, the kids tilted their heads back and watched her with the same dull hatred they channeled when they drew caricatures of her on the bathroom walls—a frizzy-haired, one-legged monster with angry, bloodshot eyes. (It was my job to scrub the walls clean, but I never had the heart to remove their artwork.) And they were hoping she’d fall—weren’t we all? —but of course she didn’t. Instead, she shimmied down the last rope and called Marie over and said, Strap it on for me, something she hadn’t said to me in years. Marie stared at Layla’s proffered stump, then snugged the leg onto the end of flesh. Her hands shook slightly, but Layla placed her own palm over Marie’s and smiled. Tighter, she said, Just like that.

*

On those overcast nights when the sea mists clung to the cliffs, and after I’d finish lotioning her stump, Layla would pull a stretch of climbing rope about my neck until I blacked out. Then I’d dream of Marie, of Marie wearing Marie. The leg would be furred in a light, mannish hair. I would stroke it, listen to Marie sigh, listen to the whisper of water outside our window, the singing of seals on the sand below. I’d float there, with Marie, with Marie wearing Marie and caressing my cheek, until Layla slapped me conscious, yelling at me that I was thinking of her again.

*

The counselors’ bunkhouse sat at the top of the far cliffs. Layla and I had our cabin at the southernmost promontory, on the very edge. (Years later, long after our divorce and bankruptcies, the sea would claim the salt-stained structure, would rise up and grab it from the eroded cliffside. You can see a video of it online still, and when I’m feeling depressed, I watch it over and over, sometimes play it at quarter-speed so I can catch sight of all we left behind, the tiny forgotten artifacts, as they tumble into the frothing waves.) A small ravine separated our cabin from the bunkhouse, but we’d strung a sturdy rope bridge across it. Layla could cross it in seconds, one-legged if she had to, and soon Marie the counselor could also. I’d be down on the beach below sorting through the safety harnesses and could make out Marie’s small form shimmying back and forth on another errand of Layla’s—she never said what exactly. In the evenings, I’d smell a lingering scent of sweat and patchouli throughout the cabin, and Layla would complain loudly about her, how worthless she was, how it’s staff like her that make South Oats lose money hand over fist. They’re takers, she’d say. That’s all they do: take, take, take.

Some nights she’d send me into town for more Madeira and yell at me to send Marie over so they could work out camp assignments some more. I’d cross the bridge by feel in the almost-dark and knock on the bunkhouse’s screen door. Layla wants you, I’d say, and Marie would roll her eyes and the other counselors would snicker. By the time I’d return, the bunkhouse would be silent and too dark to see through the screen door, to see where Marie the counselor bunked, unless the moon was low in the sky, and then I might see her legs kicked out from beneath the scratchy camp blankets we gave them, each leg luminous in that silvered light and not dirty at all. Across the ravine, our cabin would be dark also and Layla asleep atop the coverlet, her breathing slow, steady. Her stump would glisten palely and taste of lavender and salt.

*

It was near the end of the season when the accident happened. One moment, Marie the counselor was cheering a wobbling kid along the final stretch of her challenge course, a taut strand of rope only five feet above the beach—hardly high enough to worry about a fall—but then the kid was in the sand, rolling and wailing, her arm twisted beneath her. Layla limp-ran across the beach, screaming at Marie to get the kid up, but Marie only stood above the flailing body, her hands pressed against her cheeks.

Ger her up, get her up! Layla shouted, and then she was standing above the child whose cries had devolved into a series of blubbery, choking sounds like the seals that sometimes lolled on our beach.

We need an ambulance, I said.

Get her up! She’s not hurt! Layla kept saying.

Marie bent and swayed, saying nothing; she just pressed her palms further into her cheeks, sandwiching her lips together until they puffed out like one of those kissing fish.

I’m calling an ambulance, I said, already running up the beach. Over my shoulder, I saw Layla slap Marie hard across the face, knocking her to her knees, and the child quit her crying.

*

It was almost dark by the time the ambulance pulled away. Already we were getting calls and cancellations from angry parents. Layla sat rubbing Marie the leg in the dark of our bedroom. When I offered to help her remove it, she told me to get out, to go into town for more wine, or something harder, anything. Go! she shouted, and I went. On my way, I stopped by the bunkhouse and told Marie that Layla needed her. She’d changed into a scoop-necked tank top and no bra. She had small, dark nipples. Her face was no longer strawberried from Layla’s slap, but across her throat was a thin red welt. My own rope burns had mostly faded. She saw my eyes staring and gave me a disgusted look. She’s right, you are a perv, she said and pushed past me.

I didn’t get back until late. I might’ve been a little drunk. I stood outside the bunkhouse listening to the churn of waves below and watching the moon set into the ocean. It was a late summer moon, fat and sallow. Its light streamed across Marie’s empty bunk.

The next morning, Layla slapped me awake shouting that Marie was missing, for me to find her, and it took me a moment to realize she meant her leg and not the counselor, though the counselor was gone too, disappeared sometime during the night. That slut! She stole my leg! she screamed, hopping across the bedroom unsteadily, pointing to the empty chest, the key left in the lock. Call the cops, she growled, but the police were already calling us, speaking words like child endangerment and numerous complaints. And Layla crying, really turning on the waterworks, I’m the victim here! and pointing to her naked stump.

*

It was months before the leg turned up, the camp shuttered by then, and Layla far inland and not returning my calls. I found it on the beach, near the torn and graffitied South Oats sign, half-buried in the sand, its plastic toes eaten away by the grinding surf. I picked it up, brushed it clean, felt for the seam along the now pitted calf. It was rougher than I remembered, and heavier. I hurled it back into the waves as far as I could throw. This time, it didn’t float, but sank almost immediately, as if it had never been here at all.

- Published in Issue 31

IN GEOMETRY CLASS, YOU LEARNED YOU COULD DRAW by Ian Cappelli

|

an arrow at the end of a line—the assumption: that it would continue on forever. Lessons in spontaneity: old men, shirtless, doing volleyball. Somebody conceiving of a lattice bridge. Each crossbeam, in summation, holding up a road. Anglers returning an underweight fish from the line, un-arrowing the hook from its lip. Elisions accreting into distance. When pricing your mother’s records, you scan what she left you for hairlines. If something could come out of nothing, it would be a kind of evaporation. |

- Published in Issue 31

AFTER THE THIRD SNOW DAY IN A ROW, I’M READY TO THROW THE TOWEL by Julia Kolchinsky

into the fire out the window

at the cardinal clinging to the broken

branch limp like a dislocated finger

at my feet slippered & sore from keeping

up at my children yes their screaming

at my children their faces needing

always needing more

pink paper & play more water more

food different from whatever I’ve made more

more mama closer than sound lets on mama

from every room echoes the house & where

is she where? this me named need

hiding under a sodden towel ice thick

soaks frost & bitten toes thick the body

they made of me the towel too wide to noose

the towel too heavy to throw fire

just embers now barely a flash of red

through ash too weak to thaw barely the cardinal

picks at my mended bones beak tender

relentless my children

run feathered & flamed tongues stretched

for falling shards the sky lets herself throw

relentless the towel

isn’t big enough to cover all of us

mama more more mama

my children’s need relentless

& when in flight the attendants warn

put on your oxygen mask first before

assisting others how to let the body

listen when my children

inhale deep relentless

my children the only sky I know

- Published in Issue 31

THE FOREIGN JOURNALIST DID NOT HAVE TO WRITE ANYTHING NEW by Ting Lin

Raised on calcified milk, the students stood under a bridge[1].

In their hands, blank sheets of paper flutter. Nothing came

of that long season but a few good photographs. How cleanly

their faces fit into the frame of their parents. For thirty four years

there was nothing in between. When I try to fill it in the world

becomes impenetrable. The sparrows, the blackboard paintings,

red jumping rope in the courtyard. The man lying silently

in the snow like an exclamation mark. I wanted to explain

how we grew up but the deadline was up. A bluish tint

to the prints, even as it was there, then.

[1] The Beijing Sitong Bridge protests took place in 2022.

- Published in Issue 31

STUNNED AWAKE by Karen Kevorkian

Not having the book not remembering what it said

stunned awake into sheets’ tissuewrapped old dress dank from years’ saving

dusty gritty cement floor little windowless room who knew

what children could get up to

crack of sunlight outside stairs leading down to it

push open the door whatever took place still lingering

don’t you feel this way about certain spaces

you would not know what to say to who you once were

a life that could have resembled anyone’s

where your body led you too young to have imagined anything

rearing like a car alarm a sweeping fire

over dry grass where you live now

- Published in Issue 31

TWO POEMS by Kyle Okeke

Gate of Pain

Come sleep by me,

Dad says, delirious

as the hurricane taps,

then knocks, impatient—

I enter, a tall shadow

in his room, bringing him

his cup of water.

I am 20 now. I’m fine, I say.

The power will be out for days,

the branches strewn across the roads,

trees fallen into houses. Cancer

changed you. I chase a lone dog

into the street, the car almost killing

us both. The outage reminds you

of Nigeria, all you want to do

is go back: Men sinking

in and out of flashlights.

A woman roaming, asking

if I’ve seen a little boy.

Gate of Life

Quiet, says the officer

walking me to the office,

after I flashed

my knife in school—

the footsteps scuffing,

shuffling—rain-like.

All of it moving

because I am moving.

After the flood,

a quiet rose

like a shirt

off a body of land.

- Published in Issue 31

TWO POEMS by Timi Sanni

The Chronicle

At the end of my childhood, which appears

now to me in dreams as a camp, God

called each and every one of us to the hall

and handed us our griefs. “You become adult

now,” God said, a knife edge in His voice. For a

certificate, my grief was as thick as God’s Book

of Suffering. I held its hardcover catastrophe;

remembered the hard exterior of that school-

day in June when my father struck a lightning

across the clouds of my face. I bled on the

rag of memory. There was no saving nostalgia

from that impossible red. In the light of a gauze;

under a lens of steel and quartz, I examined

my past and future pain. O how difficult

it was to hold my gaze. All around me,

a papercut apocalypse. Amalgam of tears

and blood. People running into the light

of whatever innocence remained. I held still

the pen of my body; gushed no ode

to pandemonium. If time is a river rushing,

I thought, then I will mirror the heart

of my ancestors who had no word for drowning

but walked instead to the bottom of the sea.

The Trick Is

after Ellen Bass

to hide your fear of death

where even death fears to look,

which is deep inside your living,

between the risks and dumb shine,

not unlike a highway full to stupor

of damning lights and sounds.

And when death rides her pale horse

into the canyon, its hoofbeat matching

the thump of your heart; when the terror

of the age-old stones trembling

shoots up your spine,

more arrow-like than arrows,

electric, a whole fever of feelings,

and you think, Should I not now

find some stable ground?

To stand atop the leering edge,

and hold that fear like a seed, all black

stone, cold, bearing no suspicion

of the warmth of life, and say yes,

I will carry you with me.

- Published in Issue 31

DOG GHAZAL by Zakiya Cowan

The dusk’s taut silence is siphoned by a low howl fleeing a dog’s throat.

A song from deep within the bones, seething in the throat.

I remember the family dogs fighting in the kitchen. Teeth deep in the flesh coloring their mouths

with murder. Blood ran under the table, collecting like a slippery story leaving a traitorous throat.

One day, my own dog released a palm-sized mouse at my feet, and it was alive. The small, gray

animal skittered underneath the bed, tucking itself in the deepest corner, away from the throat

of the dog hungering to possess it again. After the dogs’ brawl, bodies split into meat, slowly

unraveling, the air sang of metal and bite—violence rupturing at the throat.

When my dog curls himself into the crescent moon of my legs, his breaths are as subtle

as when light winds make small breaks in still water. In the depths of dark’s throat,

his black body melts away, and he becomes rhythmic inhales and exhales against my calves,

his harp-like ribs ballooning and deflating in time with mine. A throat

opened then stapled shut is what comes of the clash. We scrubbed the floors clean of

red, the tan tile slick like a freshly coated throat.

At night, I lay between my toddler and dog, our three heartbeats fracturing the hushed stillness.

Years pass and his fur greys with age. First, a light dusting near the throat

then the speckling expands its reach like ash from a wildfire raging across a landscape.

Whether he’s lying at my feet or sprinting through the yard, I don’t forget the teeth’s throat-

splitting ability–nature’s way of revising a being, turning it from comfort to predator.

The violence can happen so quickly like an ear-ringing holler unleashed from a collared throat.

- Published in Issue 31

- 1

- 2