Lipochrome by Nathan Poole

“…God will give you blood to drink.” –Sarah Good

It did not go away—as everyone said it would. At nine months Ida was diagnosed with an obscure disorder. It was thought to be caused by an infection in the eyes at birth, a condition that amplifies the production of the rare pigments in the iris, increasing them until they dominate the eye. When most babies’ eyes shift from the lapis slate of infancy to their final and common color, Ida’s eyes turned wolf yellow and remained that way. They smoldered under her white bonnet like filament at low voltage.

This was startling to everyone. To her parents. To those who cooed at babies and drew close to see her. To those who lifted her cap to peer in at the bland, lost little face, and found those inquisitive, lupine eyes.

Soon people lost their inhibitions completely. “Can I see?” they asked, waving and jogging toward her mother across the square that divided the cemetery from the church yard, following her into stores, down the produce aisle. Ida’s mother would often turn to find a strange man standing behind her, cornering her against the lettuce. No introductions. “Mind if I have a look?”

And what could she do? She would turn her child from her shoulder, bob her on her forearm and let the stranger’s eyes stare into Ida’s, “Ain’t that a thing,” some said. “They’ll go away,” said others.

What happened when Ida was fourteen was in many ways inevitable. She had been so long an object of curiosity—a kind of unconsummated desire—and the rumors had been in the wings from the beginning, jealous and impatient understudies, anxious for their turn on stage: “I bet she has a forked tongue,” “I bet she howls at night.”

In church that morning Ida had been holding her late grandmother’s wedding band in her mouth. She was bored and had taken it off her finger and was flipping it over and over on her tongue while the reverend, a soft-eyed older man named Quatrous, was preaching the prophet Amos.

After church her mother stayed and talked while Ida wandered outside to wait on the warm church steps. From there she saw a horse standing across the street in the shade of a tremendous live oak. It was tied by the bosal to an ornamental iron fence capped with sharp hand-hammered finials. The fence had been there for a hundred years and it lifted and sunk where the roots of the oak pressed up beneath it, causing sections of finials to aim inward in concave depressions and others to fan out lethally like the rays of the sun on old celestial maps.

She was moved toward the horse by a restless feeling the church service put inside her. Like the residue a flash bulb leaves hanging in the air—an exposure that turns with you when you turn and stays out in front of you when you close your eyes—the long stillness of the hour had made the world distant and unreal and the horse was a part of the dream. She wanted to touch the tight tendons of the leg, wanted to run her hand over the muscles and across the steep hill of the flank.

As her hand neared the horse’s front shoulder it seemed a spark left her finger tips, and if not a spark, something like it, something inside her, something she carried that leapt. An invisible surface was breached. The animal spooked and reared and she fell back and watched as the horse grew tall and then taller again, impossibly tall. It came down near her, the hooves clattering on stone. A taste of iron in her mouth, a notch in the tip of her tongue. The horse went up again and she watched as it tried to clear the old iron fence. She watched as the mecate caught and she watched still as the historic finials disappeared into the smooth barrel of its underbelly.

The sound it made was significant, married to its meaning. A song lived somewhere inside the sound and it drew men toward it. From the far end of the road, and from around the corner, and from across the street, they hustled toward the sound of the horse. But the noise Ida heard had not come from the horse but from somewhere inside her. The sound was the sound of her mind when she saw the horse descend, it was the sound of a sawmill clutch before the belt gains, the sound of resistance, of wishing it could all be turned back, the sound of a loud blister in her palm after a day of raking leaves, the long wooden pews creaking, the organ growl, the doxology, pedal tones that are felt before they can be heard. It was a sound like the nameless world.

The horse’s front hooves pawed and reached for the ground while the animal remained suspended. On the sidewalk, in the shadow, it seemed the horse was running hard in a four-beat gait and the shadow was something projected out of the horse, some vital extension escaping.

The mare bled out from its barrel. Its large eye widened above her. She watched the eye as the blood left the horse, black ink streaming down the scroll work, over the nodes and twisted pickets. The big eye rolled languidly and then centered itself like the by-point globe inside her father’s liquid compass, regaining its mysterious traction to the world. She watched the eye work to stay in the world, to keep a hold on it.

Men seemed to come from everywhere then. They mobbed around her, shouting to each other, crowding in. Their boot heels slipped in the blood, streaking it with clay. They scurried around the horse’s suspended body, over the fence, placing their backs alongside the animal’s body and lifting with their legs. This was all organized by shouting and by something unspoken, the frantic purposeful feeling, not unlike joy, that men take in things terrible and unlikely.

Shouts rose suddenly to stop lifting; a man who did not hear fell to the ground beneath the horse and when he rose his dark suit pants were purple with blood and brilliant in the sunlight. The mare squealed when the lifting stopped and stamped its back legs and the men around it moved away and the horse descended only farther into the finials until it stood with its front hooves on the ground. It rested. It contemplated its pain.

Everyone on that corner knew it was Quatrous’s horse and that he had just bought it the week before. He was one of the only men in Shell Bluff to still bring a horse into town and it was only on Sundays. Quatrous made the decision. He stepped out of the church across the street and without looking twice at the scene—the men sweating, their feet slipping in the blood—he asked one of the police officers for a pistol.

Ida had been carried across the street and propped up against the trunk of a large sweet gum tree. Her eyes were glazed and the world inside her pitched and turned. Her mother took off her shoes and threw them away and held her face and stared into it and saw nothing but the vivid gold eyes, focusing on nothing. The pistol snapped, ringing the air between the short buildings, and the horse sunk entirely into the finials as a large flock of pigeons rushed out from the limbs above Ida’s head.

The women in the prayer meetings shuddered to hear each new story—though they, most of all, spread them around—and would then commence to praying for Ida and her freedom from what they called her oppression. Many believed the incident to be associated somehow with her grandmother’s wedding band and wished her to take the band off.

Ida’s grandmother had lived with them for as long as Ida could remember and her presence in their house was robust, solid, heavy with laughter. Her grandmother seemed so physical an object, and by comparison her parents, who were not affectionate people, seemed frail, as if strong laughter would sift them right out of the world like ash.

Ida would sit with the old woman in the evenings for hours and run her fingers down the large distended blue veins in her hands, tracing them as they warped over the bones, pressing them down and watching them grow faint, disappear, and then appear again. Her grandmother never resisted being touched and Ida loved this about her. She would let Ida do her hair up in all sorts of bizarre arrangements, twists and bows with confectionary zeal, everything short of cutting it, and the grandmother sat with her eyes closed, drifting in and out of sleep.

Ida was twelve when her grandmother died and her grief was immense. The wedding band was left to her for her own wedding day, but she refused to leave it in its envelope in the stationary desk. She screamed when it was asked from her and the screaming rattled her mother’s nerves. She was allowed to wear the ring, with the condition that she was only allowed to wear it on her right hand. It fit loosely on her slim fingers and Ida developed the habit of keeping that hand pursed into a fist when she walked or ran, giving her appearance a new ferocity, as if she were perpetually charging up to sock someone in the mouth.

After the horse died a series of stories developed. Desire was let free. One of the first stories that circulated throughout Shell Bluff—and even beyond, into Milledgeville and Sparta—was one that a number of people attested to seeing personally. Her grandmother’s wedding band would disappear from Ida’s finger and reappear in her throat. It happened at school. The ring appeared suddenly in her throat and was trying to choke her. Ms. Addison slapped her firmly on the back and out fell her grandmother’s ring onto the floor.

“Why’d you swalla that?” the teacher asked.

“She didn’t though,” said another girl. “It disappeared right off her finger. I saw the whole thing. It was there and then it was in her throat and she was choking. It showed up in her throat. I saw it all. I saw the lump in her throat. It’s trying to kill her.”

The word “booger” and the song, “Ida and her booger sitting in a tree…,” became a musical phrase that lived in Ida’s landscape, a bob-white’s call, a whippoorwill. The sounds of the words and the notes of the song were factual things that traveled through the air and scared her. She was oppressed. She was prayed for. All of it scared her.

Soon Ida hated being left alone, certain now, after all the words, and songs, and taunting, and prayers, that when she was alone she was not. Her fear of being alone, the fear itself, fed the rumors and as the rumors grew so did her reluctance to be around too many people, or too few, or to come near an animal, any animal, which could be difficult when almost everyone in Shell Bluff owned some number of livestock.

There were other things to reignite the story whenever it seemed to be dying down: a girl said she had a secret to tell. Her name was McCuen. She had six brothers all called by the same last name and no one knew their first names. They were McCuens. To call one was to call them all, but for Ida, McCuen was the girl who reeked of kerosene during the short Georgia winters. She was the girl who lived with her tribe of brothers and was skinned-kneed and ugly in appearance despite the fine features of her face and the way her eyelids lay softy over her almond shaped eyes, as if they were perpetually half-closed.

McCuen led Ida by the hand into the bathroom stall and instead of disclosing a secret began to softly stroke her arms, and then her cheeks, and hair. Ida felt the pressure of the girl’s hand on her head and then the hand moved to her cheek and then to her shoulder and Ida’s heart began to pound and at the same time she struggled to keep her eyes open, as if she were running full speed into sleep.

After the first kiss Ida let her lips part and McCuen kissed her again and it summed in her mind into a litany. It was a hot afternoon on a bank of red maples turning suddenly cool; it was water dripping off her fingertips, tugging each finger toward the ground with invisible force; her hand was swollen from a wasp sting, a hand that was numb and large and didn’t feel like her own when she touched it with the other; it was six pieces of coal she once found in her school desk, black like sin; it was soft like owl feathers and heavy like fruit.

They might have kissed a thousand times—it seemed an infinite space between each one. She never kissed back but it did not matter, she did not have to. They came one after the other. There was another girl there who saw them standing together, who had walked in quietly behind them and saw their shoes staggered in, facing each other. And she could tell, she just could, by the position of their feet and the odd silence, and she knew what was happening. It was this girl, hurt with longing and self-consciousness, who told her mother what she had not seen but knew, who told her friends that she had seen what she had not, who told everyone she could that Ida had seduced McCuen with her witch eyes. Then she added to the story as it needed adding, added that she heard them speaking together, in one voice speaking, and that they spoke in a language she had never heard before.

Ida’s parents received visitors who offered their advice, who spoke of how they had cured their own children from similar dispositions. McCuen spent two weeks out of school and no one knows what happened to her those two weeks, but when she returned to school she never looked at Ida again.

A few months passed and Ida was exhausted and numb to everything. She avoided animals completely, certain that whatever was with her would scare them, cause them to jump off of cliffs or hurl themselves on sharp objects.

Ida would be made a member of the church in early August. She completed her membership class uneventfully and the date was printed in the church bulletin with the names of the other children to be made members. The following week Ida’s named stood alone and the other baptisms were all rescheduled.

On the afternoon of the event Ida was picked up along with her family by a tall young man with greasy hair who drove a long pink Buick convertible. He introduced himself as Jimmy. Jimmy had just come down from Columbia with his new wife and was excited to be part of the occasion. On hearing from his brother-in-law that there would be a baptism he insisted on driving the family. He treated them like prominent figures in a grand parade. He left the top down on the Buick. He spoke loudly, over the radio—which he did not turn down, even as he pulled into the church parking lot to meet the caravan that contained the minister and what seemed a large number of cars and trucks that would follow them to the river. Compared to her father’s truck, the Buick went smoothly, suggesting the familiar road with its washed out creeks and roots while transcending it. Soon the other cars in their party were no longer visible. Ida gave up tucking her hair behind her ears and let it swirl around her face while her mother kept both her hands on her hat and her father wore his dark suit and a tight smile across his embarrassed face.

“I remember my first baptism,” Jimmy yelled at his passengers. “I thought the man wouldn’t ever let me up and when I did get up I tried to sock him in the face. He was messing with me. I swore he was. He looked small to me and I thought I could take him but he was strong as an ox. God. He was strong. He threw me right down again into the water and held me there until I gave up.” He reached back and slapped Ida on the leg and laughed as the Buick veered slowly toward the tree line. He corrected into the road and aimed the rearview mirror at her. “So don’t try it,” he winked.

“I thought you said you didn’t baptize till you married Q’s little sister.” Ida yelled back.

“Honey, that’s not your place,” her father turned.

“I didn’t.” Jimmy said.

“But you were baptized as a little boy?” she asked.

“Honey,” her father said again.

“That’s true,” he declared, laughing, “I got baptized as a boy but didn’t get saved till I married Q’s sister. I guess I was on layaway.”

Jimmy’s laughter caused the limbs to shake overhead and the light to spill down through the trees. He had tears in his eyes he was laughing so hard and the car was swerving and Ida felt herself being made new. Thurston Harris’s Litty Bitty was playing on the radio and the music was infecting them all. A strange sense of buoyancy entered her bones. She would walk across the water, she would bob like a cork. They smiled as they looked at each other, a family but strangers to themselves, figures made from air and sugar and gossamer, confections from a dream.

Baptisms were carried out in an eddy along the Savannah River where it takes Miller’s Pond Creek. There is a sandy wash a few steps up the creek mouth with good shallow clear water and the current is soft. Quatrous often said he loved the spot. It reminded him of those lesser-known lines from Cloverdale: “Lead me forth beside the waters of comfort.” “You see, the water doesn’t need to be still,” he would say on a Sunday morning, “‘Cause the best water keeps on moving, don’t it. You go get a drink from Telfair pond up above the dam and tell me it don’t taste like a slick froggy. Now go get you a drink from Keysville at the head and you’ll lay yourself face down and say Lord have mercy. Good water knows it’s not done. It’s got a race to run along the earth. Amen? It’s not home. No. But it’s bringing home with it, just not there yet. Who else ain’t home? We aren’t. That’s right.”

As the cars pulled up they could already see it wouldn’t do. The river was swollen and banking violently. The party walked the upstream path together in a single file just to see how the creek mouth looked and it didn’t look any better. What had once been an eddy was a brown churning place. Every so often a log would drift in and spin a few times like it was in a washer and then shoot back out into the river.

The men stood on the bank watching the river surge by, already intoxicated by the level sheen of light—if only it were small enough for them to run their hand across it, like a table top, to examine it, they would. Quatrous took off his shoes and rolled up his pant legs and prepared to wade in a few feet where it seemed the slowest. He needed to see how bad it actually was before he would give up his spot.

“Easy now,” Jimmy said, laughing.

“Woooo,” Quatrous said to the crowd, widening his eyes. They laughed.

“Is it cold enough?” Jimmy yelled.

“Woooo,” he said again, “no, it’s tugging though. It’s tugging.”

He waded back carefully and reached his hand up to Jimmy to help him step out just as he slipped in the slick kaolin clay that banded the bank. He went down on his face before he could get his hand down and the current pulled him immediately out of the creek mouth. As it did he rolled casually onto his back as if he were expecting as much to happen. It seemed like his belly was made of cork the way he shot out into the Savannah, bobbing in the rapids as he accelerated. He was cruising very quickly out of sight, disappearing in the shade of large maples and hickories and then reappearing on the other side moving faster than he was before and then he was gone.

Ida and Jimmy were racing along the bank shouting with others, Jimmy running ahead and laughing so hard he could barely keep Quatrous in sight. Ida’s feet slapped along the packed footpath. She caught glimpses of Quatrous, down low close to the bank. He would occasionally roll onto his stomach and reach for a branch overhead and then, having missed it, roll back onto his back to look where he was heading. When there wasn’t a limb to reach for he kept his arms down by his side and used them as paddles to direct himself.

After two or three attempts he finally got hold of a low hanging Possumhaw limb and was immediately stretched out longways downstream so that he couldn’t get his feet underneath him to walk out for fear of increasing the drag and breaking the branch. They all moved to go down when Jimmy grabbed Ida by the arm and said, “No sugar, you stand right here.” He made her hold onto a skinny tree and nodded to confirm that she would not leave it. He and another man went down the steep bank carefully together holding onto washed out tupelo roots.

“You finished bathing?” he yelled down to Quatrous.

“I’m just thinking,” Quatrous said.

“About how to get out?”

“No. About what it means.”

“It means you’re a clumsy old man, is what it means.”

“Maybe. Maybe,” he said, the water streaming around his face, framing his red skin. His thin white hair pasted and pulsing on his brow like a jelly fish.

“Do you want to hear my plan?” Jimmy said.

“Go ahead then.”

“I’m gonna hold onto this tree with one hand and put the other on your arm and when you stand up the current is going to swing us around and pull you into bank and then you can grab onto those roots over there. How’s that sound?”

“Sounds like a plan.”

The rest of the party arrived as Quatrous was crawling carefully up the bank on his hands and knees and Jimmy was making his way up alongside, holding onto the trunks of trees, practically climbing from one to another. Ida’s father held Quatrous under the arm as he stood. The preacher took off his tie and rang it out. “Well, where to?” he said. “We might as well do this while I’m still wet.”

Ida was baptized in a pond off Claxton-Lively road. It was fed by an aquifer and it was the coldest water she could ever remember being in. He put her under and the water ran across her chest and she thought she felt her heart stop. When he pulled her back up she was shivering so hard she couldn’t walk. Quatrous lifted her and carried her out of the pond and she sat down in the hot sand beside it while waves of dizziness, something near ecstasy, shot through her mind and body. The sun warmed her and she thought of nothing and it was in the nothing that the figures and voices of her life swung around her like a globe of stars being cranked and she heard the sound of the Buick’s radio and she felt the heavy light entering her again, an opening in her mind, the opening of a fist.

It had been a little over a year since the horse had died and Quatrous thought it was time to bring her near an animal again. He thought they might give it a few tries, thought he would even teach her to ride and that the sight of her up on a horse would be good for the neighbors to see.

The Latvian was a heavier animal, good for light draft work and riding and above all, calm as a tortoise. Ada was already standing when she saw Quatrous walking the animal around the bend in the road. Her dress was clinched in a ball in one fist above her knee, her other hand on the door knob. Her eyes were wide and tracked the horse fiercely as they came. She stood like a deer at the edge of heavy woods, every nerve balanced. As soon as Quatrous turned up their long drive and it became clear he meant to visit the house she ducked inside.

He knocked on the door.

“Ida, come out here and meet this lady, she’s real sweet.”

He waited. He heard Ida and her mother talking softly.

“You want to know her name? Abigail. That’s sweet, isn’t?”

“Go on,” her mother said.

Quatrous left the door and went down to the animal and petted it and pulled an apple from his pocket and feed it a bite and pulled the apple back.

“Want to feed her this apple?” he called.

Ida came out with an uncertain look on her face and took the apple carefully, keeping her eyes on the horse like it was a blasting cap.

“Go on,” Quatrous said. He motioned with his hand to show her how to lift the apple up. She watched the motion from the corner of her eye and lifted her hand up.

The horse took a step forward, moving her mouth out toward the apple. Ida pulled the apple back quickly and then launched it across the yard into the garden. The horse turned to watch the apple fly and when it turned back to her she caught it on the side of its nose with her closed fist. The Latvian’s eyes grew wide. She slapped it several more times with her palm as it turned from her in a trot. She screamed and caught it once more on the flank with the flat of her hand, sending it into a steady gait out of the yard toward the road. A truck coming down the lane slammed on its brakes to let it pass in front. The horse swerved tight around the truck’s hood, almost colliding with the fender before heading off in the opposite direction along the creek bed. It looked as if it would run the rest of the way home if home wasn’t in the opposite direction. The mother screamed after her daughter but Ida did not stop. She disappeared after the horse, the newly long legs pawing the ground with incredible speed. “I’ll grab the truck,” her mother said. She went quickly inside the house. The screen door slammed.

Quatrous walked calmly out of the yard with his hands stuffed down in his pockets. His head down.

“Damn it,” he said to himself.

As he came to the road he saw the hoofprints where they turned up the packed earth and he saw the ring lying brightly beside the spot in a slick of mud. He put his boot heel on top of it and pressed it down deep as if it were the head of snake. He kicked some earth over the spot to trod it down a second time and waited there for Ida’s mother.

Issue 6 Contents NEXT: Singing Backup by Jason Kapcala

|

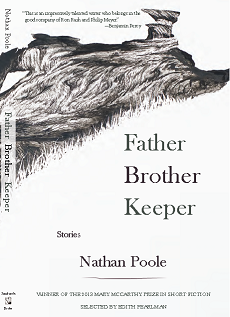

“ Father Brother Keeper is marvelous. To read the work of Nathan Poole is to discover an immense, beautiful secret, rich with private histories and the rhythms of our complex, haunted world. These are stories to cherish, a debut to celebrate.” ~ Paul Yoon Available February 15 from Sarabande Books |