SEPTEMBER INTERVIEW with LIZA HUDOCK

Addiction, death, and loss are everywhere in Liza Hudock’s debut collection, Reveille (released by Flood Editions in August), but they are not its actual subject. Instead, the poems wrestle—as near as it can be stated—with the world the speaker inhabits. Whether she turns her attention to a moth, the comparison between a pumpkin and a sonnet, Renaissance art, or a spoon, Hudock’s syntax and images are as surprising as they are breathtaking in their clarity and freshness as she explores, among other things, what it means to give care to people and places that may not be able to be healed.

FWR: I wonder if you could start by talking about the title of your book, which is the title of one of the later poems in the collection—how did you choose the title, or how did it choose itself?

LH: On military bases (and at summer camps, if the movies are true) reveille is the bugle call played at 7 am, usually as a recording over a PA system (it comes from the French command réveillez-vous; wake up). I either heard or pressed play on “reveille” almost every day that I was in the Coast Guard, and that experience did bring the word to my vocabulary, but it isn’t why I chose the title. My youngest sister used to throw water at the sparrows who lived in the bushes near our house when their chatter annoyed her. They hadn’t bothered me before, but I noticed them a lot more after she died. One morning, I picked up the copper pot she used to use for water throwing and I just brandished it in the birds’ direction, and they fell silent.

A few months later, I heard a concerto for choir by Georgy Sviridov called “Pushkin’s Garland”. One of the movements is called “Reveille.” The lyrics for this movement are taken from a Pushkin poem called “The Dawn is Struck.” I liked the figure of dawn as shorthand for the bell that is struck at dawn. I imagined the way a beam of light strikes a brass bell and the way that brightness has the sudden intensity of a bugle blast. So, this “Reveille” felt connected to the silence that rung out from my copper pot that day. That’s how I titled the poem. And then, it was just clear that it should be the title of the book.

Reveille does a lot of lamentation for my mother and sister, but I hope it feels full of possibility, like a new day—and by possibility, I don’t necessarily mean optimism; you can wake up full of fear, but certainty that the day must be different from the one before can be enough.

FWR: Let’s talk about influence. You mention Whitman, Stevens, Dante and Genesis in the book. Who would you say are your most important literary and/or artistic influences?

LH: Christine Kitano gave a lecture on poetic lineage while we were working on our MFAs—I’m sure you remember it, and I recommend it to everyone. That lecture is the foundation of my understanding of poetic influence and the reason I was able to find a voice for these poems. Basically, it’s okay that the pantheon of poets living in my heart is not upheld by any single school or tradition. I am the connective tissue. Part of my struggle starting out was that I felt like I was writing from nowhere and I needed to locate my voice somewhere in order to begin. My poetic lineage, which I didn’t realize I had built through years of reading until Christine talked about the fact that it was a thing, gave me the origin point I was missing. And, also, the lineage changes with me: Zbigniew Herbert, Wanda Coleman, Marianne Moore, Francis Bacon… I lived with them during those years. Before that, I read everything Pevear and Volokhonsky have translated from Russian. Lately, it’s been Dionne Brand and Fanny Howe. I’ve been reading The Faerie Queene almost every day… I don’t know why.

FWR: I’d also like to discuss visual influences and elements in your work. There are two ekphrastic poems in the collection: “After Mantegna’s Lamentation of Christ” and the gorgeous “After the Gold Leaves from Pelinna,” as well as a few other poems that describe or look at religious icons; your visual imagery is precise and stunning throughout the collection. (In the “Mantegna” poem, for instance, I love seeing the “whorled lake/ like a marble slab” and “the pads of [Christ’s] washed feet,/ torn skin like a gull’s/ wings in flight.”) Indeed, one of the hallmarks of this collection is your command of simile, image, and extended metaphor. I’m quite shy of similes in my own work because it’s so easy to write a hamfisted simile, and so hard to write one that really surprises and changes one’s way of seeing. But you jump right in, and after looking at them over and over again, I think they work because they are, when taken all together, intelligible, surprising, and mysterious—even when you work with an extended metaphor you’ll finish with a turn to something that resonates and opens up meaning without fixing it and snapping the poem and its meanings shut.

I think here, for instance, of “My Dead Folks Know They’re Dead.” In the wake of her losses, the speaker acknowledges a freedom that “Like a tulip/ […] comes fastened/ to the buried fist that feeds it, or the leaf/ that nourishes the fist.” At the end of the poem the speaker turns to her own “Mind// worming away at things, certain only/ of the first thing I said. The way/ I know the hard bulb by its tulip.” I’m still mulling all of the possibilities in these comparisons!

I want to ask, “how the heck do you do it?” but I suspect the answer is that it’s just how your brain works! So instead I’ll ask, is this a conscious process? Does it grow out of your precise observations of the natural and human worlds, or do you begin with the idea or state that you’re comparing to the vehicle you write about?

LH: My process grew from reading Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s poem, “Closing Time; Iskandariya.” It was the most perfect example of description I had read to that point and therefore one of the best poems I had ever read. I decided that if I could just look at whatever was in front of me and describe it, the words that came would be enough for a poem.

I wondered if the urgency of Reveille was a little unhealthy, by the way. It would have been appropriate for me to take a break from writing and then come back to the book about the year my mom and sister died with a measure of artistic distance. But you know Nietzsche’s famous sentence: “And if you look long enough into the abyss, the abyss will look into you,” right? I recently discovered the sentence that precedes it: “Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster.” That’s exactly what was happening to me. I was bitter, treating life like a joke. Something compelled me to work on my descriptions every day, and that practice preserved whatever cooling coal of tenderness I had left for the future. So, the intention to describe was conscious. Figuration is the natural result of the effort to describe. I have an aversion to all that “like” too, but I did it anyway. Fortunately, my process has changed. Figuration is still there, but more vaporous.

FWR: I’m curious about how you think about craft, in part because we attended the same MFA program and studied with some of the same poets (though our aesthetics and approach are quite disparate—which is one of the reasons why I always love to talk about poetry with you!). What formal and structural elements do you particularly pay attention to in your poems, and is form something that you think about early in the composition process or that you arrive at when the poem starts to find its way?

LH: I don’t know about you, but I absolutely needed to learn craft. Getting an education didn’t ruin anything for me, if that’s what you mean. The wildness and the mysteries are still here. I think of structure in terms of syntax, and I do cast and recast a poem in different syntaxes until it feels right. Form, as in the shape of the poem on the page, is usually the last thing figured out. I will begin with such a clear vision of a prose block, and then it turns out the poem was destined to be long and skinny, for example. I handwrite until the words of a poem are pretty much settled and then send it through all kinds of forms once it’s on a screen. This can take years, but it seems a matter of dignity to find the shape a poem is waiting for.

FWR: Could you walk me through your process in a particular poem where the form went through this kind of evolution?

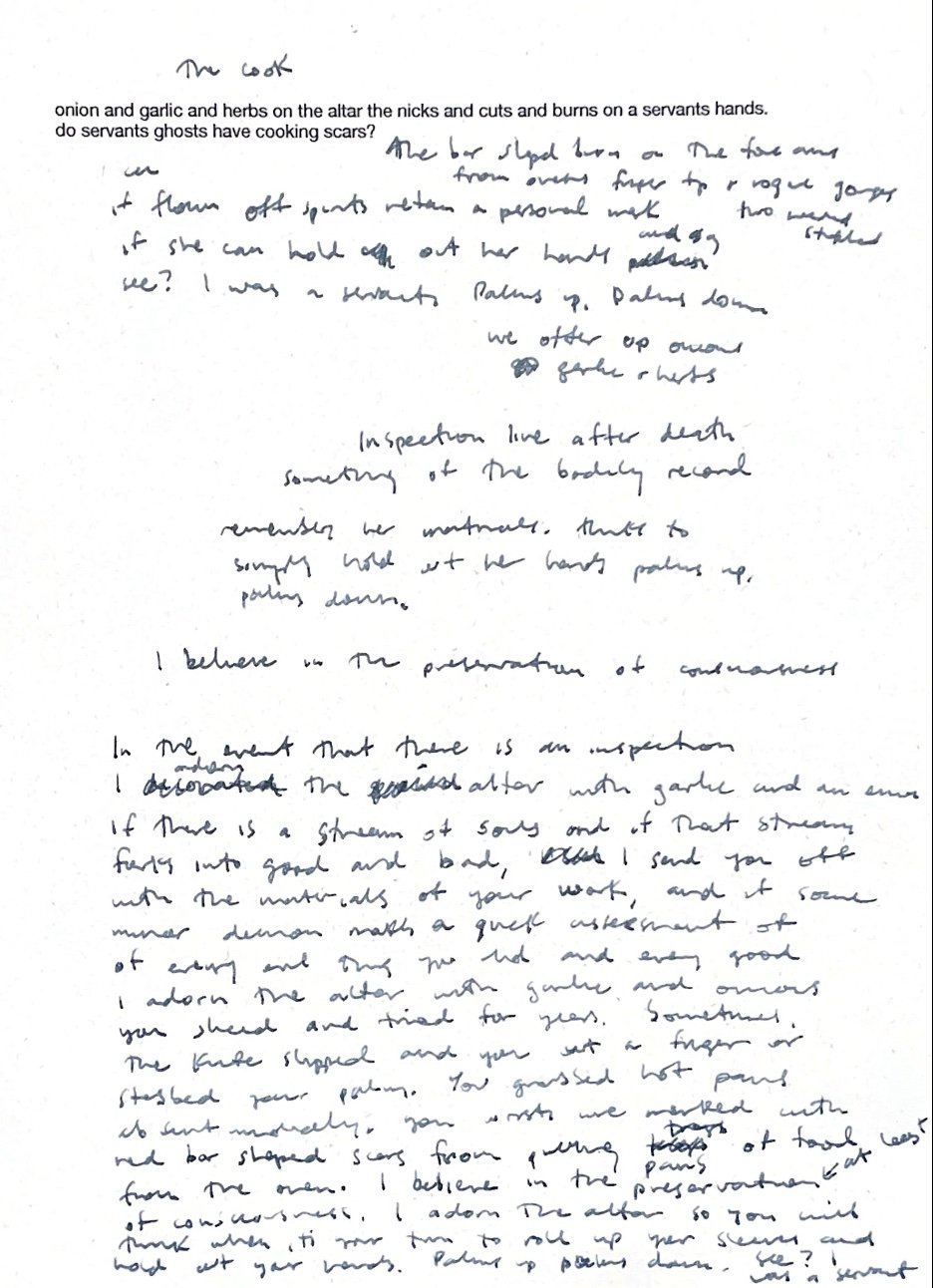

LH: Yes: for example, the first draft of “Funeral for a Cook” existed for a few months as just this short note. I printed it out on its own sheet of paper feeling that it might become a poem. A few more notes, and suddenly I was cramming the words in as a prose block to make it fit on one page. Once I re-typed the poem, I didn’t save the many formal variations it went through, but I can describe a couple. This poem is a loving gesture with a volta towards the end, so I tried typing it as a sonnet, but that wasn’t right. My favorite sonnets appear to discover themselves as they unfold; they feel surprised by their own turns. “Funeral for a Cook” seems to know its ending from the first word. The poem just wants the reader to trust it enough to follow.

Next, I noticed a couple strings of iambs that worked well as short lines, so I tried to type the whole poem in 3- to 4-beat lines and favored end rhyme where I could. In this form, most of the short lines cut against the syntax too much. I didn’t need the added tension between line break and syntax in a poem whose proposition was already so tenuous. It turned out to be a very willful, line-driven poem. The lines work like rungs on a ladder, allowing the speaker to advance her desperate imperative with a strange sure-footedness. Generally, if a line isn’t end-stopped with a period, it breaks at the end of a clause or otherwise natural breathing place. So, once I let each line defend itself as well as possible and allowed stanzas to group thoughts in a way that only strengthened the poem’s rhetoric, I landed on the shape that now feels inevitable.

FUNERAL FOR A COOK

In the event you come up for inspection,

I lay the altar with garlic and an onion.

If there is a stream of souls that forks into good and bad,

I send you to it with the materials of your work.

In case some minor demon makes a quick assessment

of all your evil deeds against the good,

I lay the altar with the garlic and onions you sliced and fried.

Sometimes the knife slipped.

You cut your fingers and stabbed your palms.

You grabbed hot pans daydreaming,

your wrists were lined with red scars

from the oven’s opening.

I want to believe in the preservation of consciousness.

I lay the altar so you might think,

if you are ever to be judged, to roll up your sleeves.

Hold your hands out and I promise never to tell you

what to do again.

Hold your hands out. Palms up, palms down:

see? I was a servant.

FWR: I’m fascinated by all of this, especially the way you noticed what wasn’t working about each form even as you recognized the impulse that drove that version. And, for the record, going back to your previous answer: yes—I absolutely did need to learn craft too! I had read and written a lot before the program, but I kind of rebuilt my understanding of poetry, both as a reader and a writer, from the ground up. Which brings me to where you are now: what is your writing routine like; what does your writing (and/or revision) process look like for you, and has it changed since completing this book?

LH: I don’t have a routine as far as time of day or length of time. I do tend to work in batches. I’ll have several poems laying out like wet canvases and sometimes I spend hours with them, sometimes I just make a change to one on my way to something else. The process of writing Reveille doesn’t seem repeatable. It took place in stages. At first, my sister and I were sleeping every other day, tending to our mom constantly. We did her hospice at home. I wrote down an image if I could and just promised myself to get back to it. Our youngest sister died eight months after our mother. So, Reveille dwelt amongst cortisol and insomnia and grief. I sensed the window to write it was going to be brief, and it was.

FWR: How long did it take to write the book? Are you working on anything now, and, if so, does it speak to Reveille in any particular way?

LH: I wrote most of it in 6 months and revised for another 6 months, but this fruitful year came after 2 years of… maybe a different kind of fruit. Just learning. The poems I’m working on now are less narrative, less sequential. More imaginary. An image and a phrase will arrive as a pair and I find out how they know each other. Some of their forms are new to me, too. The Reveille years had a theme color and it was yellow—even though yellow is a happy color and that was a sorrowful time.

Now, I’m rejoicing, I have a baby, and the prevailing color of the poems is purple. I think purple and see a forbidden forest. I was puzzling over this last spring and noticed that for a few weeks, there were just dandelions in the grass, then violets appeared among the dandelions. It’s just the natural sequence. One follows the other, they go together. So, maybe the connection between my yellow and purple poems is as simple as that.