I AM SORRY THAT I NEVER SAID GOODBYE by Pegah Ouji

I was helping my roommates, hanging up a pumpkin balloon for Halloween, when I got your text message saying you were in town. This was my first American Halloween away from my parents, far from Farsi, a world of English consonants, sour cream and meatloaf. I started typing in English, inviting you to the party, but immediately deleted it, retyped it in Farsi because I was always puzzled by English. How do you throw a party? Does it have corners you can grip? Where is it to be thrown?

You answered in English, Cool, I’m down.

I didn’t tell you but your black overcoat reminded me of the Mantou we wore in fear of the Morality Police in Iran. When I hugged you at the door, your eyes held the same distant look as if you were always looking above us all, into some galaxy where a new star was being born.

You didn’t want to dance so we sat in a corner on the gray shaggy carpet that always felt moist. I had asked you about life in LA, you had shrugged and said something I couldn’t hear in the hubbub of the music and the shuffling bodies, couldn’t even read your lips in that dimly lit room.

It was all too much; the loud music, sweating bodies stuffed in costumed- witches, superwomen, batmen- swaying to American songs I had never heard before, beats that didn’t move my body like a song of Andi could.

After whispering in your ears, I will be right back, I left the living room and retreated to my bedroom downstairs in the basement. I felt that just a few minutes of lying down on my cool bedroom carpet was all I needed as a recharge before I could subject my senses to the sensory assault again. To be honest, I was also overwhelmed to see you again, after all these years. We had parted as children, our last hugs exchanged in Tehran and now here, adults in a strange land.

Our families used to go camping in the wilderness around Shiraz. Remember the time we sat close, holding hands, sweat glistening our laced palms as we watched that mother goat give birth to her baby? Remember the slick, wet skin of the baby, as its mother licked it a few times, that shake of its hind legs as it tried to stand, and fell, over and over. Remember the newness of life, the fresh scent of a mammal’s first milk?

Walking back up the stairs, I resolved myself to ask if you wanted to leave the party, go for a walk around the block. But you were already gone, disappearing like the thin smoke of your father’s old motorcycle exhaust.

I am sorry I never said goodbye.

Now that you are gone forever, our friendship feels unfinished, a run-on sentence that will never benefit from the peace of a period.

For days after hearing the news, I tried to close my eyes, recall back that evening, and reconstruct the movement of your lips. What had you said when I asked, “How do you find LA?” “It’s alright. But I miss Iran. Or “It’s fantastic, I never want to go back to Iran.” Whatever the case, I knew you had said the name of our country, which also happened to be the name of your grandmother and perhaps you were just telling me about her and nothing more.

Now I will never know what thoughts went through your mind at those late hours of the night when the demons we bury in the day rise again restless, when we become porous, thoughts wiggling through like starving worms. Words. I would never hear slip out of your mouth again.

During our camping trips to Iran, words were all we exchanged, planning our futures, our Iranian husbands, you were going to become a pediatrician, saving lives of little ones. I wanted to become a chef, to cook meals that melted in mouths, that bound hearts. What does immigration do to us when someone like you, brown eyes brimming with the promise of tomorrows, turns into a twenty-year-old girl who takes her own life? There is English again, exasperating my confusion. What does it mean to take a life? Where is it taken to? If it is taken somewhere, can it be brought back? In Farsi, the news of your passing would be just that, passing, dying, unadorned, ugly, harsh, cold, moist carpet, a mother goat licking its placenta after the pangs of birth.

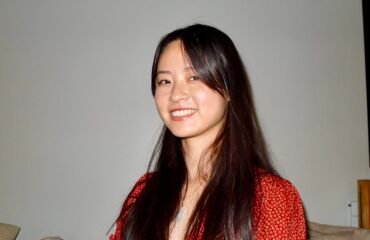

I checked on your mom’s Facebook page every day for two months, where every day she posted a photo of you, sometimes the same ones, you always smiling, words arrested in your mouth, your long hair draped over your shoulders, your eyes always looking off from the camera. Were you really beholding a realm beyond ours? Because when I think of you, my demons resurrect, it’s dark in my mind, and we are back at the party, crunching on popcorn and Oreos, and I am always asking you, how are you? And I am always staying put, never leaving, listening, hanging on to every word escaping your lips as if it were the last word I would ever hear from you.

In my mind, you’re always alive, and I’m a baker, serving you the sweetest saffron cake, both of us watching, from the branches of a mango tree, that baby goat taking its first wobbly steps into a new life, full of possibilities.